In California, ODDS made their first appearance in state legislation in 2017 with the passage of SB 35, which enabled a streamlined approval process for infill multifamily and mixed-use residential projects proposed in places that have not made sufficient progress toward their regional housing need allocation (RHNA). Since then, ODDS have been included in several other California bills seeking to remove procedural barriers to new housing projects (SB 330 and AB 2668) and expand the geography where multifamily housing projects can be allowed (SB 9, SB 6, and AB 2011). And requirements for ODDS have spread to other states as well, including Washington’s recent HB 1293, requiring ODDS in design review, and HB 1110, enabling 2-4 units on every residential lot subject solely to ODDS.

The California Government Code defines Objective standards as standards that “involve no personal or subjective judgement by a public official and are uniformly verifiable by reference to an external and uniform benchmark or criterion available and knowable by both the development applicant or proponent and the public official before submittal.” In short, objective standards need to be clear and measurable, in contrast to subjective design guidelines that many places depend on today. ODDS can include zoning development standards (regulating the zoning envelope), always include design standards (regulating elements typically addressed during design review) and can also include subdivision standards (regulating the subdivision of land).

As a replacement for design guidelines and discretionary review processes that are often unpredictable as to time and outcomes, ODDS seek to provide certainty for all involved stakeholders when housing projects meet the requirements. This is accomplished through more predictable and easier to interpret standards that don’t rely on public officials’ meetings to discern what’s required. ODDS also seek to produce more housing, (something that jurisdictions across the US have struggled to do) by avoiding the arbitrary reduction of the zoning envelope—and subsequent reduction in housing units—for subjective reasons like a project being “too dense,” providing insufficient “light and air,” or damaging “neighborhood character”: common, often unfounded complaints about proposed developments that end up reducing housing production.

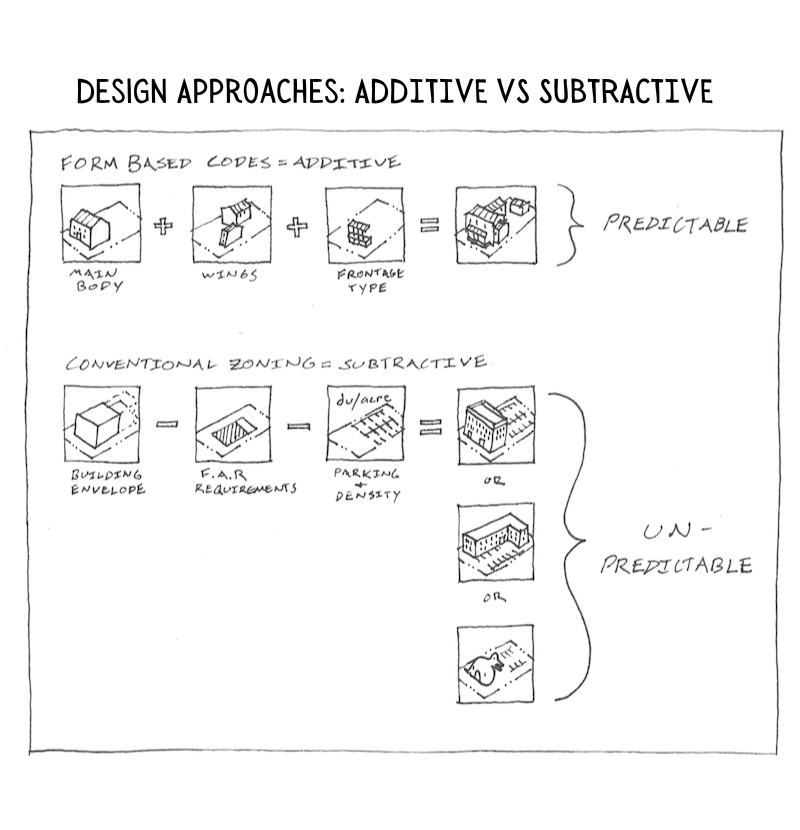

ODDS Have Roots in Form-Based Codes

Objective Standards follow strategies established by Form-Based Codes. In fact, one could say they are their direct descendant, as FBCs were introduced to enable walkable, mixed-use places where new housing projects can thrive, and FBCs, like ODDs, include “verifiable and measurable standards” to streamline development. In California, FBCs made their way into the Government Code in 2004, after advocates called for FBCs as a solution to the worsening housing shortage. Since then, they have been adopted in a variety of ways, as part of both Specific and Master Plans and widely used to regulate infill and revitalization projects in priority development areas across the country. Now, in California and beyond, under new State laws, many cities are looking to expand objective, form-based controls over much larger geographies.

ODDS Help to Produce Housing

Many California cities have recently drafted and adopted ODDS. And approvals of by-right housing projects have increased: a recent Terner Center study documents 156 projects and over 18,000 housing units approved under SB 35 (requiring ODDS) alone between 2018 and 2021.

Seeing this strong connection between ODDS and housing production, State legislators are advocating for ODDS, more housing developments are being approved under them, and it appears that ODDS are here to stay. But adopted ODDS vary widely, ranging from very simple 2–3-page ordinances, to lengthy and detailed examples that provide sometimes meticulous and detailed guidance on exterior elements, materials, and even colors. And despite FBC’s long history dating back to the late 1980s, many planners have not had first-hand experience with a form-based approach, and dissenting opinions and questions on ODDS remain. How should communities approach ODDS, and how detailed should they be?

Opinions of ODDS Vary

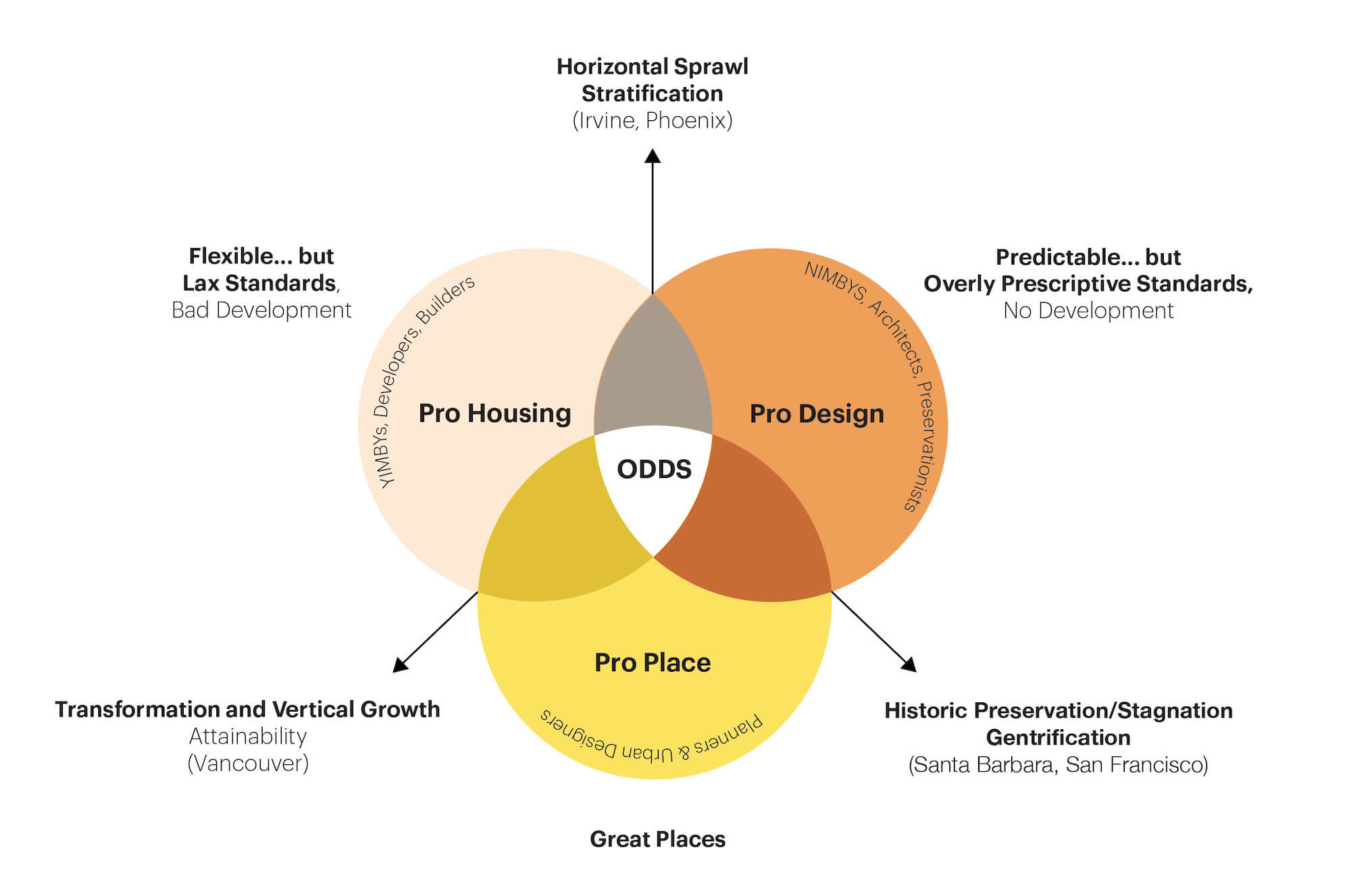

On one hand, many who are wary of ODDS advocate for a minimalist approach including many in the “pro-housing” camp: Housing advocates like YIMBYs (Yes in My Backyard), developers, and builders, who want to ensure that ODDS don’t present a barrier to feasible development. Keep ODDS simple, they say, so developments will require minimal changes and projects can be built with speed and efficiency. But this position sometimes comes at the expense of historic preservation and community character, and – let’s face it – there is a long legacy of destroying great places that communities held dear in the name of new development.

Many neighborhood groups and review boards who are not “pro-housing” also share skepticism, because of the role ODDS play in enabling by-right housing projects and the loss of local control. These groups might take a “pro-design” position but are not excited about new development; they include NIMBYs (Not in My Backyard) and others who want to see existing neighborhoods preserved just the way they are. Either do everything you can to prevent ODDS from being adopted, keeping discretionary processes in place, they say, or make standards so complicated that they effectively become a barrier to new development. But this position has often come at the expense of new development, contributing greatly to a national housing shortage that’s resulted in increasing unaffordability, inequity, and financial uncertainty for many.

A third point of view, shared by many planners, urban designers, community advocates and others who are “pro-place” see ODDS as a necessary tool. They want to ensure that ODDS enable new development, but are extensive enough to preserve local character, enhance rather than degrade neighborhoods, and result in compatible development. This camp is wary of a loss of quality and character that might occur, especially in the absence of discretionary review, and sees ODDS as a kind of insurance policy against bad development. Better to make sure ODDS cover anything and everything, they say, just in case.

Successful ODDS need to find a balance between these different groups – they need to be prescriptive enough that they can sustain and make great places in a predictable way, while flexible enough that designers and developers can respond with creativity to produce housing. It’s important to note that this balance is not the same for every community. Some places look for a lot of oversight and discretion in new development and expect ODDS to be more comprehensive and detailed. Other places prefer a more laissez-faire attitude that gives more freedom to applicants and their designers and may want a simpler approach.

City Planners often find themselves in the middle of this conversation, whether it is mediating between groups to find the “sweet spot” for ODDS in their community, whether they are writing ODDS or applying them during development review. Standards can impact development feasibility, architectural design, and placemaking, all of which are not in every Planner’s skillset. Adding to this situation, streamlined review means that much of the professional expertise found on Planning Commissions and Design Review Boards may no longer be available. Some early proponents of FBCs even advocated for Town Architects to provide code administration rather than Planners, because the thinking at the time was that they simply were not well equipped to facilitate streamlined review on their own.

ODDS are part of a larger sea change in how communities review and approve development and how housing occurs in cities, and regardless of their level of complexity, ODDS need to be well-understood and clear for Planners to administer because they are the front-line implementers in all scenarios.

Rather than seeing ODDS as an obstacle to housing production, ODDS should be seen as an opportunity for Planners to engage in housing production, placemaking and community design to a greater extent than they often do now.

In our next post, we’ll share some ways Planners can use ODDS to do just that.

Completed

Marin County, CA Objective Design + Development Standards Toolkit

- Adopted: Belvedere, Corte Madera, Larkspur, San Anselmo

- Sausalito adoption expected by Summer 2024

Puget Sound, WA Regional Missing Middle Zoning Toolkit & Resources – in process of being used by individual cities

Campbell, CA – adopted

Citrus Heights, CA

Los Altos, CA – adopted

Orinda, CA – adopted

Richmond, CA – adopted

Santa Barbara, CA – adoption expected

Sebastopol, CA – adopted

In-progress

Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) Handbook on Preparing ODDS ready for cities to use by April 25, 2024

Folsom, CA – adoption expected by September 2024

Mountain View, CA

Santa Rosa, CA