Start With an Understanding of Place

Before drafting ODDS, start with an understanding of the physical form and character of the places where they will apply. In conventional, use-based zoning it is not always apparent what physical outcomes are expected, especially when housing may be introduced to places for the first time (like adding residential uses to a commercial zone, for example), or where new housing is expected to alter the character of existing places (like adding multistory housing to an existing single-family zone).

As communities have had to expand the geography where housing is allowed, either because of State Law requirements, or to meet regional housing needs, it is often done without visioning or thought of what kinds of places should emerge. For example, many communities have policies to include multifamily as a land use in commercial and mixed-use areas, but lack information that provides direction as to the form and character of new development.

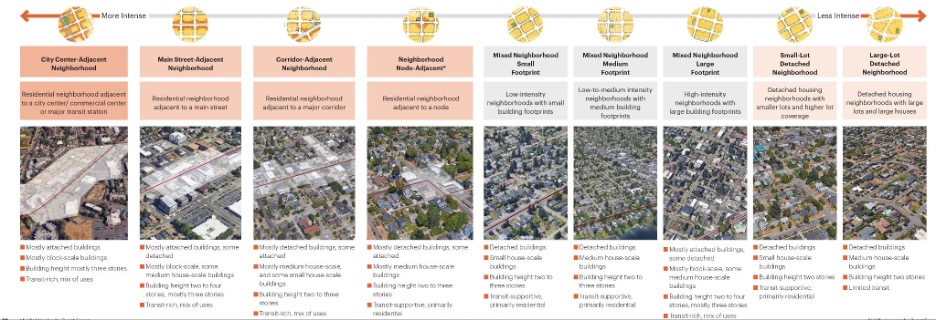

And communities are rarely one-size-fits-all. So, this work needs to begin with a careful analysis of the repeating physical environments that make up existing places followed closely by thinking about how much change is expected in each area. The result of this type of thinking? Place Types. Place Types are helpful because they provide a kind of shorthand that can help to identify the desired physical character while setting expectations about how much change is expected, and communicating the range of zoning and design standards that will be needed. For example, are infill buildings expected to be mixed-use, placed at or closely behind the sidewalk, and attached? Or are infill buildings expected to fit into an existing pattern of detached, house-scaled buildings, with consistent front and side yards?

Choose the level of regulation that’s right for your community (Hint: it might not be as much as you think).

ODDS, especially in communities that like to have a lot of oversight, can sometimes be extensive and detailed. But too often neither the intent, the rationale, nor the expected outcome of applying design and development standards is clear. With a lot of adopted standards circulating, in the interest of efficiency and checking another state mandate off the list, many standards end up being copied from place to place. Or worse, jurisdictions take a buffet approach to all of these standards that are circulating. Before long, many things quickly trend toward complicated, and become what is universally accepted and normal, despite a lack of understanding of what might be really needed.

One example is requirements to get “variation” in building facades through the application of recesses, required offsets, and projections at specific intervals. It is widely accepted by communities, often as a way to “objectify” subjective guidelines that promote “variation” and “diversity” in building design. But do these kinds of standards really help to produce well-designed buildings? Do existing, well-loved buildings have this articulation? How much of this is “enough,” and in what situations is this kind of regulation necessary, to create good buildings and places?

These can be particularly tough questions for Planners to answer when ODDS address things like building elements that are typically outside their purview.

Understanding place and context can empower Planners to determine what’s essential, what can be considered optional, and “why” and “where” certain standards are needed. For example, façade variation might be important when large buildings are expected in places where transitions to smaller existing buildings are desired, or where very large parcels are expected to redevelop. But in other situations where large buildings are expected to make “block-scale” environments, or where narrow parcels already provide variation, such transitions may not be necessary, and these kinds of standards may not be needed. In both situations, ODDS can do a better job of communicating the clear intent and outcome of the standards, and the kinds of places the standards are expected to make.

Even when taking the detailed route, it’s still important to be intentional around what – and how – design elements are regulated. Many cities, for example, look for detailed regulations for architectural design to encourage architectural diversity and variety. Rather than assume this means an overly prescriptive, creativity-crushing approach, cities can take this as an opportunity to regulate only the essential elements that reflect repeating patterns valued by the community to which architects can creatively respond. For example, in a mixed-use environment of attached historic buildings that are 40 feet wide, a new building much larger than that could be required to design facades of similar width (not style) to contribute to the existing pattern and physical character. Or in a neighborhood, a community might decide to require deep eave overhangs because the area that they are regulating has a pattern of these kind of roofs. New buildings could then propose many compliant outcomes, provided they meet the required depth in the objective standard.

Build in Flexibility

When ODDS are detailed and prescriptive it’s sometimes difficult to meet every standard exactly as its written. This can discourage investment in new housing, or create situations where applicants are compelled to ask for relief, resulting in much less predictable outcomes. ODDS can provide flexibility in many ways. One way forward is to describe a range of outcomes from which applicants can choose. For example, a range of building frontage types allowed in a zone means that applicants can select from one or more of them to best meet the conditions of their development. In exchange, the applicant knows that their selected type and its standards when applied to their building will be approved. Built-in choices are recommended instead of the well-known situation where an applicant is required to meet a ground-floor retail requirement in a place that can’t support it; one in which complying with the standards might result in a storefront that might remain empty, or, if relief is granted, might be a blank, inactivated wall at street level.

Objective standards can also benefit from adjustments, which allow deviations from certain numerical standards in specific situations. Perhaps there are conditions on a given site – like excessive slope, a heritage tree, or a utility line – that make compliance with particular standards difficult? Adjustments that are coordinated with key (not everything in the ODDS) standards can help Planners determine when a deviation should be justified and how far a standard can be stretched without compromising place, all the while keeping development review streamlined.

Be prepared to evolve, update, and expand ODDS

Trends to streamline development review and broaden geographies for by-right housing across the country mean ODDS are likely here to stay. ODDS can help communities be pro-housing, enabling streamlining and housing feasibility, and pro-place, ensuring development makes neighborhoods that are beautiful, walkable, and human-scaled. Getting them right can mean finding the right balance between flexibility and predictability, and new housing that results in better places for everyone.

As Planners leverage ODDS to step into a new, placemaking and community design role, it’s important to learn from their application, and as with any tool, periodically review how the standards are working, and update them in response. Planners can also expect policymakers to continue to expand the geography where housing will be allowed. This means that ODDS should not only be organized in such a way that are easy and straightforward to amend, but that ODDS should be easily applied to other areas in your community when the time is right.

Whether working with individual communities to make ODDS or developing Toolkits to apply ODDS across regions, our work at Opticos seeks to empower planners to enable great places. If your community is ready to make or update ODDS we are eager to connect with you.

Completed

Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) Handbook on Preparing ODDS – published April 2024

Marin County, CA Objective Design + Development Standards Toolkit

- Adopted: Belvedere, Corte Madera, Larkspur, San Anselmo

- Sausalito adoption expected by Summer 2024

Puget Sound, WA Regional Missing Middle Zoning Toolkit & Resources – in process of being used by individual cities

Campbell, CA – adopted

Citrus Heights, CA

Los Altos, CA – adopted

Orinda, CA – adopted

Richmond, CA – adopted

Santa Barbara, CA – adoption expected

Sebastopol, CA – adopted

In-progress

Folsom, CA – adoption expected by September 2024

Mountain View, CA

Santa Rosa, CA