In each article, we cover each mistake one at a time, discuss why each is important to avoid, and provide graphic examples of both good and bad solutions, as well as even better approaches. This series is not meant to specifically call out certain cities, states, or efforts, but as constructive criticism designed to help more cities and states get it right. Missed the first article? Read our previous post to learn about MMH Mistake #1.

Missing Middle Mistake #2: Treating the number of units per lot the same as housing types

The second mistake is treating the number of units per lot the same as housing types. It’s important to understand and be able to communicate about the different Missing Middle Housing types because each type has an intended form and scale, in addition to having an implied number of units. It’s not just simply about allowing a higher number of units per lot, but rather wanting units per lot to have a specific form and scale that reinforce a thoughtful approach to housing type design and neighborhood design.

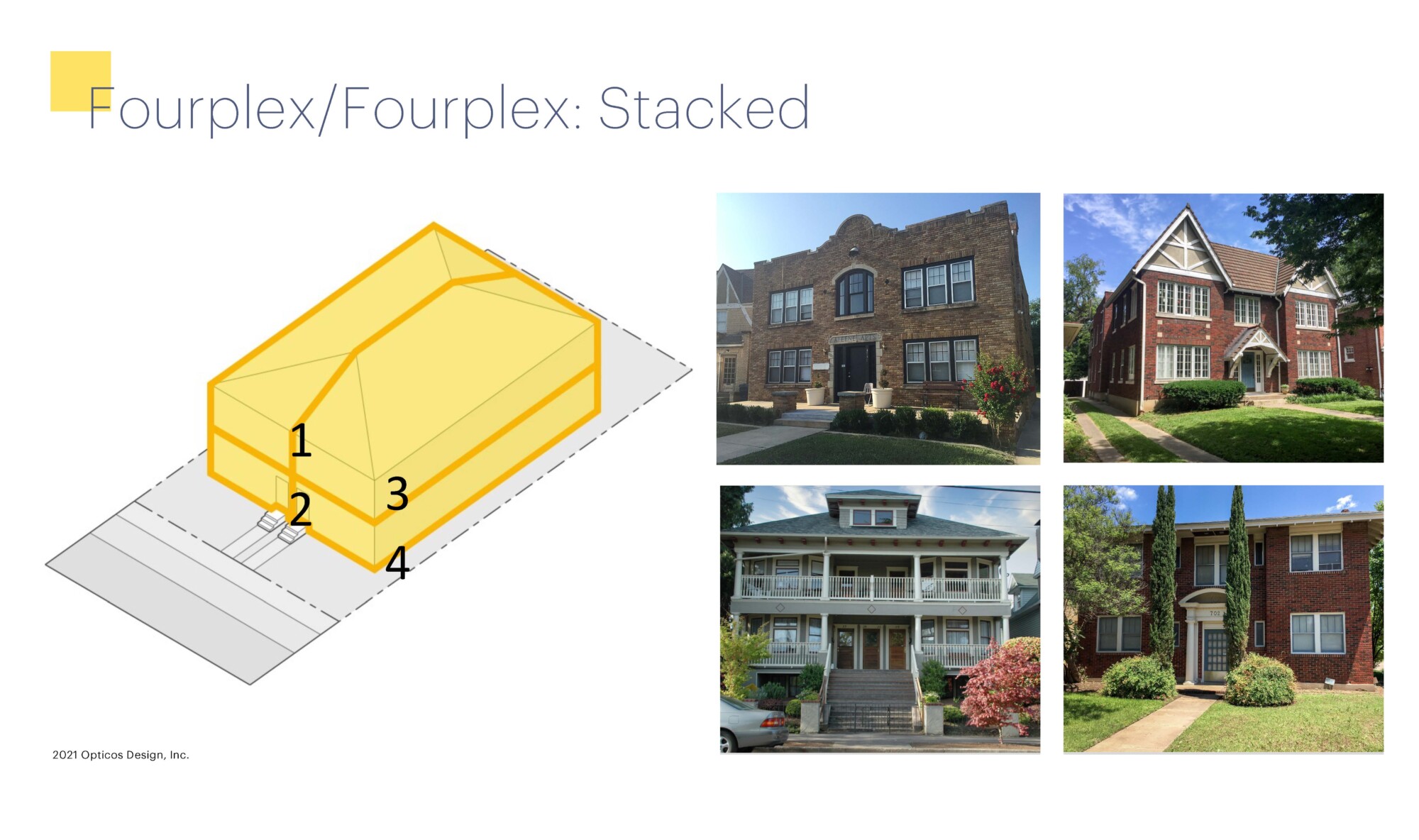

When writing my book, Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis, we refined the names of different housing types. One of my favorite missing middle types is what we’ve started calling the Fourplex Stacked. It can be found in pretty much every neighborhood built prior to the 1940s with two units on the ground side by side with the same two units up above, mirrored.

Through years of research and analysis, I have documented the characteristics of this housing type as well as all of the other Missing Middle Housing types, and I encourage cities to use these as reference points when thinking about what types to allow, how this type fits on lots typical in your community, and how that can inform the zoning to allow for thoughtful form and scale.

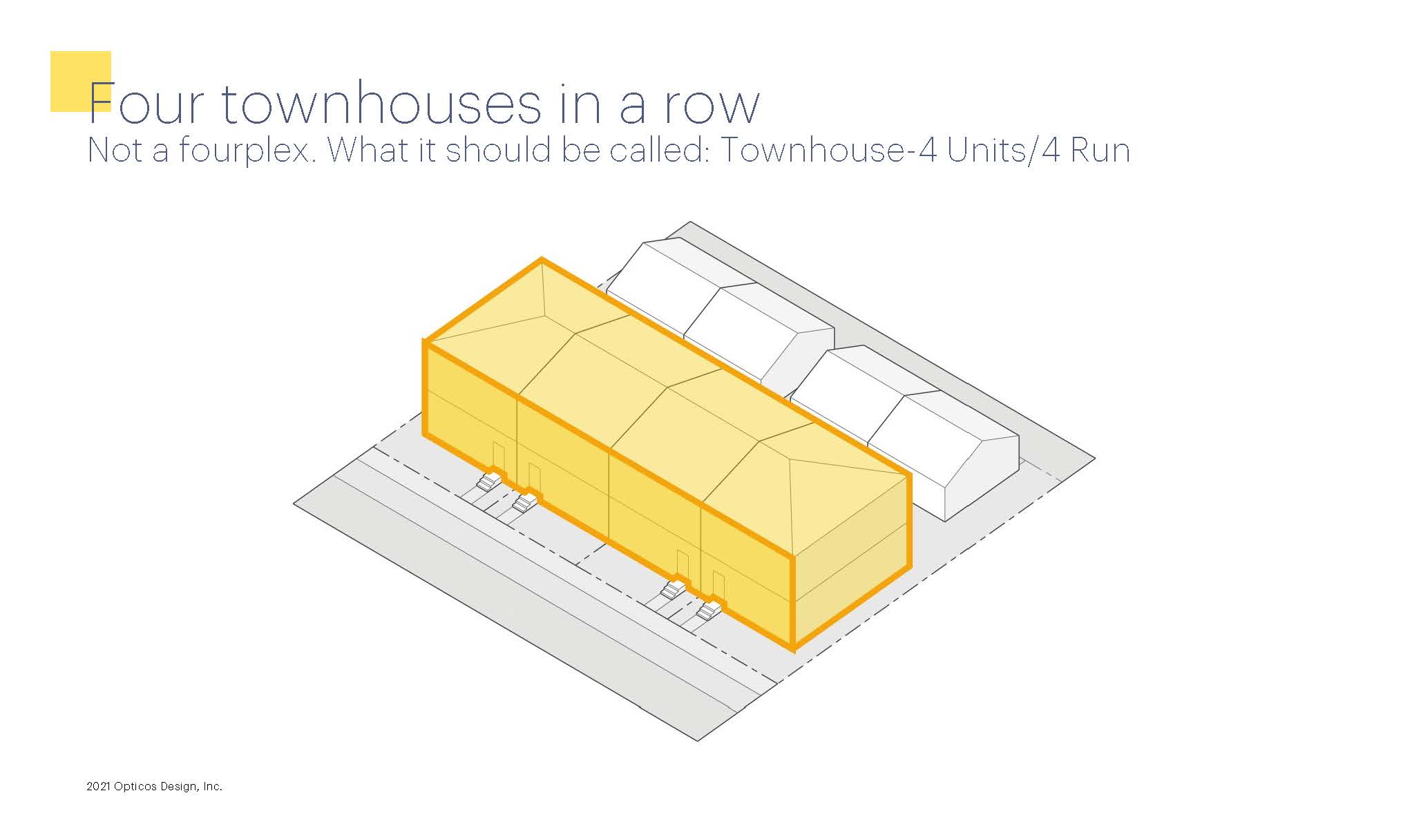

In comparison to a Fourplex Stacked, there are plenty of examples of four units on a lot that I do not consider to be a fourplex. While a townhouse is a good missing middle type, we often see four townhouses attached being called a fourplex. For the sake of clarity, I prefer to reference this as a four-unit townhouse run. It’s important to differentiate it from a fourplex because the built result is different and has different implications.

Another example is a single lot that contains four single family homes. Once again, in my mind this is not a fourplex, it is four separate units that make up a house cluster. It’s not an end result that I like to promote as it does not deliver attainability. While a single example on a block might look fine, when thinking about the evolution of a typical block over the course of 10-20 years, having that type replicated numerous times in the same area doesn’t create a desirable final outcome. I want cities and counties going through this process to be thoughtful about where they allow these built results.

Missing middle types imply a specific form and scale. For example, a duplex is not just two units per lot. In my book, I’ve broken down the duplex type into subtypes; there is a single story, side by side type and a stacked version. Cities may want to create a specific classification for the stacked type which has one unit on the ground floor and another unit up above. It’s a great type for cities and neighborhoods that have existing narrower lots. It’s common for variation on these duplex types to happen locally or regionally, but they all maintain house scale and preserve rear yard space which help structure good urban form and a walkable neighborhood.

Ultimately, planners need to shift their focus from building type to desired form.

During a zoning process that Opticos led in Austin, Texas, community members noted that they really liked single story, side by side duplexes. However the zoning wasn’t being regulated thoughtfully and the community had ended up with a zone that allowed two units per lot, but instead of getting that great side by side duplex with smaller attainable units, they were getting two full size single family houses per lot. Cities need to be thoughtful about how to allow a duplex, which types of duplexes are allowed and think carefully about the implication of the end results. Ultimately, planners need to shift their focus from building type to desired form.

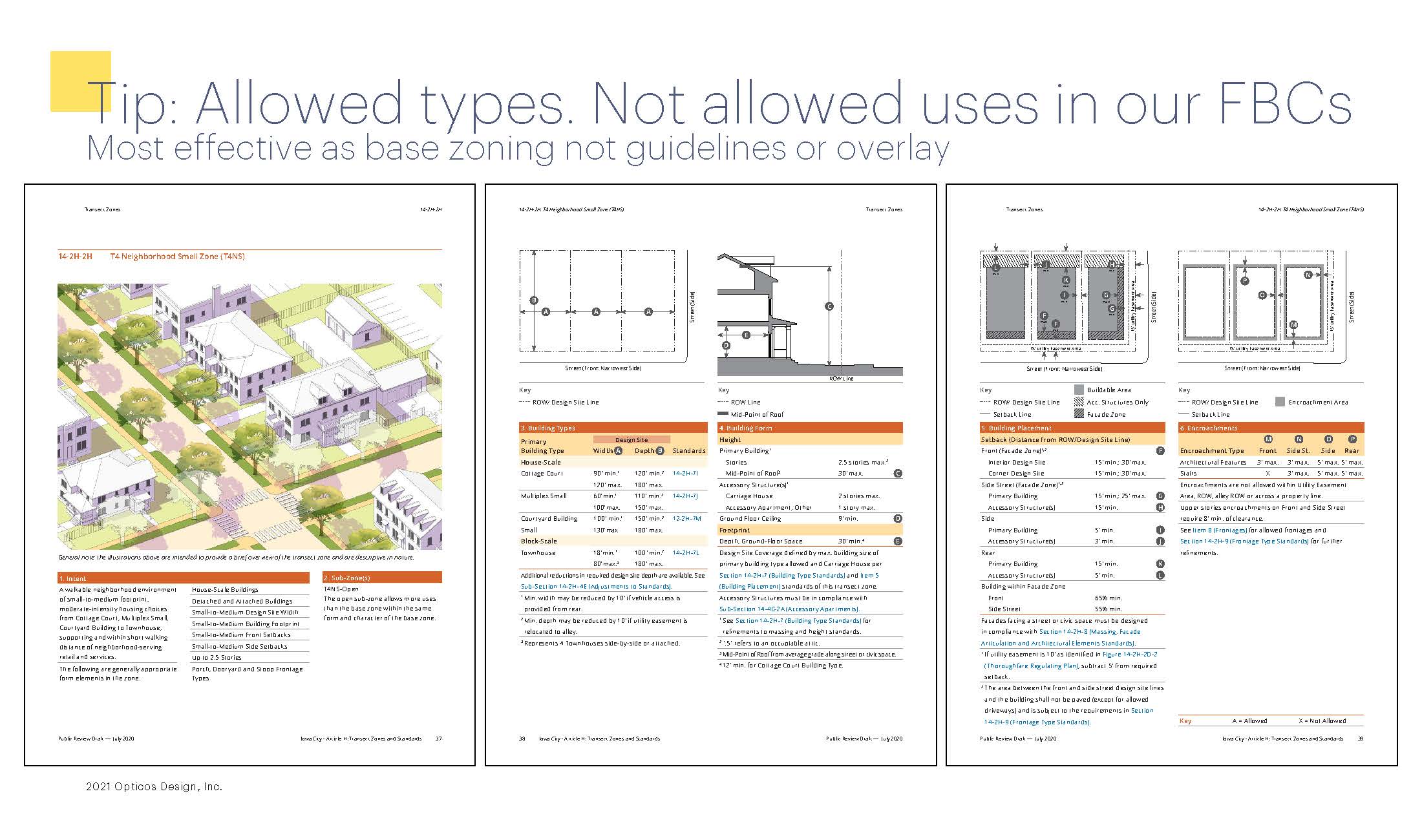

While working with Iowa City, Iowa, we created a new zoning district. It specifically identifies which Missing Middle Housing types are allowed in that zoning district, as well as what the maximum building sizes are. The most effective approaches to Missing Middle Housing replace or make targeted refinements to targeted zoning, as opposed to adding guidelines or overlays on top of existing zoning. That tends to make zoning more complex rather than allowing for clarity to deliver more missing middle types.

Remember the goal of Missing Middle Housing is to create housing choice—house-scale buildings in a walkable neighborhood— and to use zoning effectively to allow for and encourage attainability and affordability of the new housing that is desperately needed across the country. We don’t want to make existing zoning more complex and we don’t want to approach the housing crisis from only a density-led perspective. Continue reading our MMH Mistakes series to discover MMH Mistake #3.

Are you interested in implementing Missing Middle Housing types in your city or town? One of the first steps we encourage you to take is to complete an MMH Scan™. This service identifies where a city should prioritize Missing Middle applications and identifies the specific barriers to implementation. It’s a significant first step that can inform a comprehensive plan. Contact us to learn more.

Up Next:

In the following three parts of this five-part series, we’ll discuss Mistakes #3-5 and potential solutions for each.