The primary reason behind writing “Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to today’s Housing Crisis.”, and launching www.missingmiddlehousing.com as a free online resource, is because we want to see every town, city and state be successful when implementing Missing Middle Housing.

It has been rewarding to see the concept of Missing Middle Housing spread over the last several years and to recognize how broadly it is being discussed and applied. However, I am concerned by what I’m seeing with regards to the policy and zoning reform associated with implementing Missing Middle Housing.

Based on personal experience, approximately only one of every five cities and states are implementing missing middle correctly. More than once, I have found myself in conversation with city staff having to inform them that their newly rewritten zoning codes do not have the right metrics to effectively regulate Missing Middle Housing. Sometimes minimum lot sizes are too large or densities are too low, other times setbacks are too high or parking requirements make development infeasible.

My concern is that if the initial built results over the next five years are underwhelming or do not deliver attainability, it will draw backlash from community residents. There was similar backlash in the 1970s and 1980s when most downtown-adjacent neighborhoods were rezoned to allow for dingbat apartments; those boxy, two or three-story apartments suspended over street-level parking. In many cases this led to drastic downzoning that allowed for only single-family homes, even in areas that had multifamily zoning.

Why are new zoning codes not effectively regulating Missing Middle Housing?

If there was a simple solution, much more Missing Middle Housing would have been built over the past few decades. To put it bluntly, not all planners and zoning code writers have the right skill set to effectively plan and zone for the effective delivery of these types. If they did, Missing Middle Housing wouldn’t be “missing.” I admit that there is a long list of barriers impeding the delivery of these housing types. Cities need to get the zoning right to enable an ecosystem of builders to evolve, local banks to get comfortable financing these types, and other barriers to systematically be removed. Getting the zoning right first is the most important step to correctly implement Missing Middle Housing.

My intent is to discourage efforts that are well-intended but don’t successfully deliver quality Missing Middle Housing. Encouraging a more thoughtful and refined approach to achieve these goals will make it easier for missing middle projects to get approved and lead to long-term success and support for this application, rather than continued push back and opposition.

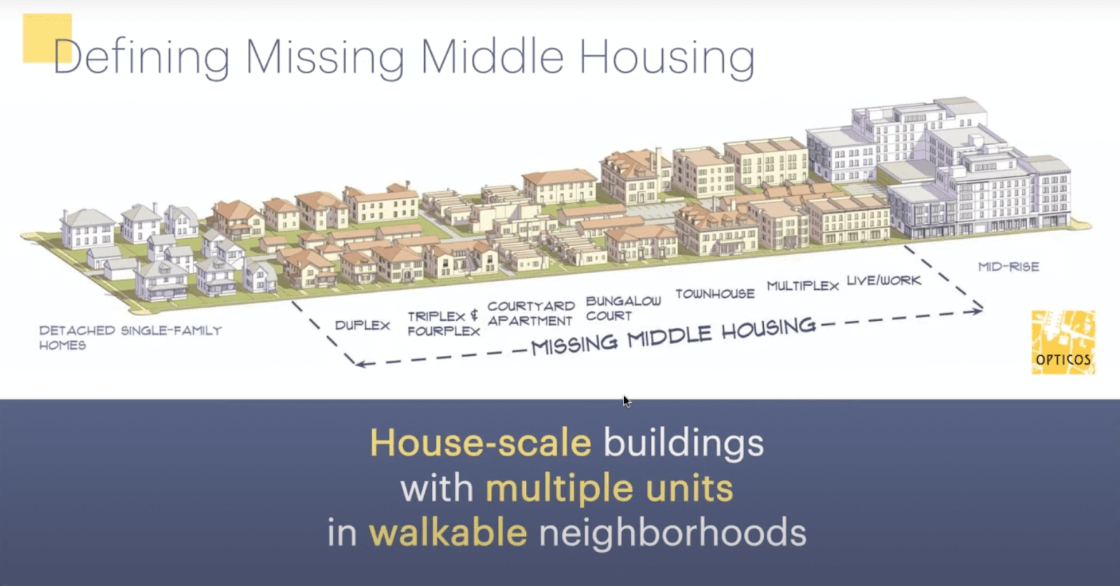

Defining Missing Middle Housing:

I want to reinforce that a very important aspect of the concept of Missing Middle Housing, as we define it, is thoughtful form and scale (livability), or what we often call “house scale.” This concept is not about simply creating more density. These “house scale” types of multiple-unit buildings have historically delivered attainability and are also in high demand from a growing number of households that do not want to live in single family homes. We need to deliver these housing types to meet the need and demand.

In this series, I will introduce the top five mistakes cities and states make with regards to regulating Missing Middle Housing. We’ll cover each mistake one at a time, discuss why each is important to avoid, and provide graphic examples of both good and bad solutions, as well as even better approaches. I am not doing this to specifically call out certain cities, states, or efforts, but I may do that if I need to make a strong point. This constructive criticism is designed to help more cities and states get it right.

Mistake #1: Allowing types/ build out scenarios that do not deliver attainability or livability

What not to allow:

Slot Homes or Multiple, Full-Sized Single Family Homes on One Lot

What are slot homes?

Slot homes are a bad variation of townhouses that are perpendicular to the street and have an extruded 3-story building envelope that goes from the front setback all the way to the rear setback with no breaks in the form. The name of this built result was used first in Denver, Colorado.

There was significant opposition to this built form after the city changed their zoning in a way that allowed for these types. After a few years of built results, community members fought to stop more from being built and Denver ultimately changed their zoning to not allow this type. But they did it in a thoughtful way that allows for similar development potential/overall square footage, just in a better built form. The better missing middle configuration can easily achieve the same densities and may actually be higher density, but in a more compatible form.

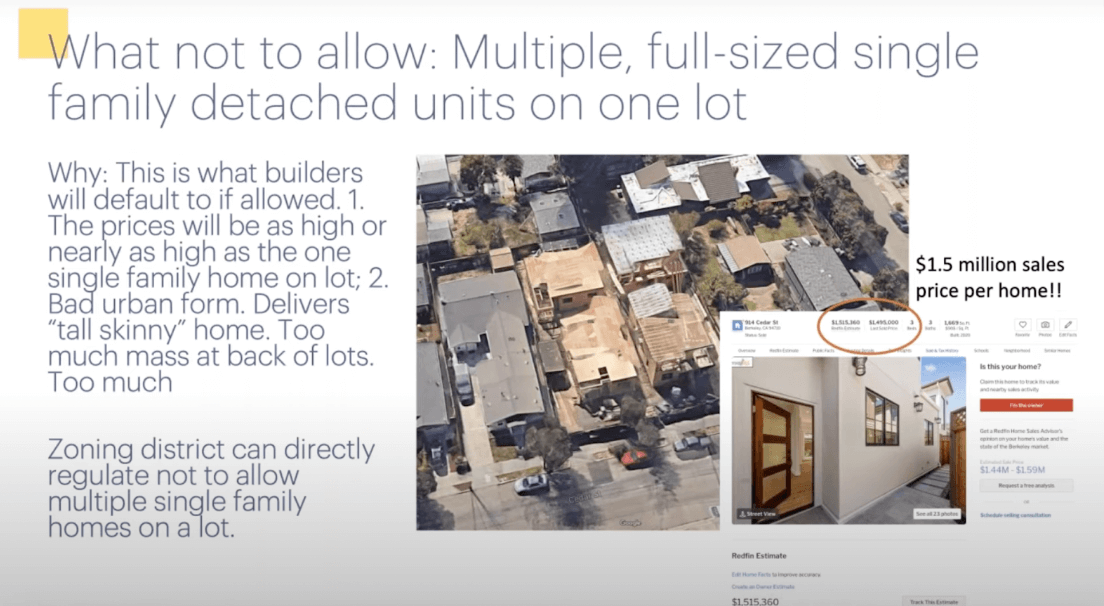

What are Multiple, Full-Sized Single Family Detached Homes on One Lot?

A full-sized home can be defined as a home that is 1,200 square feet or bigger. In this scenario, one single family home is purchased, torn down, and replaced by three to four, often 3-story, single family homes. You have seen these “tall skinnies,” and they often stick out like sore thumbs in an existing neighborhood when they are built as infill.

If you allow builders to deliver these “tall skinnies” this is likely the only new housing you are going to get in your city. It is the easiest transition for builders to make from conventional single-family homes.

To give builders and developers some cover, condo liability is a major issue in some states for the alternative of small, missing middle-scale condo buildings. This is an obstacle we need to figure out how to remove in order to encourage more delivery of Missing Middle Housing.

What Is Wrong With The Above Build Out Scenarios?

They Will Not Deliver Attainable Price Points:

It is important for cities and states to prohibit the aforementioned build out scenarios or they won’t be able to deliver attainability or more housing at affordable price points. The research done by the Brookings Institute for the article, Gentle Density, uses a sample site in the Washington, D.C. metro to demonstrate that when tearing down a single-family home, even replacing it with townhouses does not deliver attainable price points.

I have seen examples in my hometown of Berkeley, CA where a developer has bought an existing home for $1.2 million, torn it down, and proceeds to build four homes on the lot that each sell for $1.4 million. I know these price points may be shocking to many, but you can translate these to other markets where values are not as high.

They Deliver Low Livability/ Bad Neighborhood Form:

Livability relates to quality of life for both those living within the new homes, as well as livability of adjacent homes. While this may not initially seem like a bad solution, a block with even half of the lots built out this way would be very unappealing. Here is why:

1. Low quality, Leftover private or shared spaces for the homes:

In these build out scenarios there is very little usable outdoor space left between buildings. It’s leftover space rather than thoughtfully designed space and has poor natural light. It’s also not engaged by living spaces as a majority of the first floor is often designated for parking, relegating living spaces to the 2nd floor.

Many examples, particularly slot homes, have narrow, canyon-like spaces that lead to entries but aren’t conducive for spending time in. Again, good build outs and the regulations requiring good housing types can deliver high-quality, smaller shared spaces without compromising development potential.

2. Unbroken mass from front to rear of the lot (Bulk at rear of lot):

The continuous, unbroken three-story form, from front setback to the rear setback, is a stark difference from existing form and scale and does not reinforce the “house form” scale inherent in missing middle types.

This also means the build out pushes a three-story mass of the homes to the rear of lots, often to the rear setbacks that are often 5-10 feet from a rear property line. These examples tend to meet lot coverage standards, mostly because the necessary driveway area is enough to meet the standard, rather than meeting the intent of leaving some usable outdoor space.

3. The massing looms over adjoining neighbors:

Unlike good infill types, which have their primary window facing onto the street and/or to the rear yard, with secondary windows facing to the side and adjoining properties, these units are three stories with a majority of units on one entire façade from the front to the rear of the lot facing directly at and over adjacent properties to the sides of the lot.

4. Dead ground floor and bad frontage on street:

In both build out scenarios, most of the ground floor is dead space, while the living spaces typically occur above the ground level. This leaves little activation at street level. Even if the design is mitigated with a small porch or stoop, it is not likely going to be used. If the living space is all the way up on the second floor, are you really going to walk down a flight of stairs just to sit on your front porch or stoop?

5. The build-out creates an unlivable and undesirable block form:

This potential build-out needs to be assessed on an individual lot scale, and also considered in terms of its impact across an entire block. It may take 20-30 years for the majority of an existing block to change.

Historically, the missing middle pattern, when referencing the concept of “house scale,” stopped at a certain lot depth. It left high quality shared or private space, which mitigated concerns about privacy in rear yards and created open, undeveloped space at the block center.

Highly desirable urban neighborhoods in cities such as London, San Francisco, and Brooklyn have this mid-block green space that allows for tree canopy, water filtration, and peace of mind. It maximizes livability in urban places while still delivering good urbanism.

Missing Middle is not a one size fits all solution.

Missing middle is not a one size fits all solution. We often suggest considering three degrees of change: 1. Maintenance; 2. Evolution; and 3. Transformation. In neighborhoods that are targeted for transformation, a larger form and scale are more appropriate, even if they contrast with the existing form and scale. In evolving neighborhoods, the form and scale should be less of a stark change from the existing scale.

One of the important characteristics of Missing Middle Housing types is that they demonstrate how you can achieve more attainable housing in house scale buildings than in conventional apartment buildings, especially if you are integrating smaller units. Some specific neighborhoods, like those with historic designations, are best categorized with a maintenance degree of change that calls for very little change in form and scale. In these types of markets, like most of California where the cost of housing has become so high, there may be few areas within cities with this defined degree of change.

Once again, it’s important to reinforce that this information is in no way intended to provide ammunition for community members to push back on the delivery of much-needed housing. It is intended to give cities and states the tools to effectively deliver attainable and livable Missing Middle Housing.

Up Next:

In the following four parts of this five-part series, we’ll go discuss mistakes 2-5 and potential solutions for each. Stay tuned!

- Missing Middle Mistake 2 – Treating the number of units per lot the same as housing types

- Missing Middle Mistake 3 – Limiting the number of units per lot versus regulating a desired form

- Missing Middle Mistake 4 – Not effectively regulating form and scale to ensure “house scale”

- Missing Middle Mistake 5 – Not effectively addressing parking requirements as a barrier