Recap of Building Types Parts 1 & 2

In Part 1, we noted that few of today’s zoning codes recognize the historically diverse palette of distinct building types found in our most walkable and beloved neighborhoods. Instead, zoning codes typically use a blunt system of regulating buildings by their current use, their setbacks, and often by other clumsy measures such as density and floor-to-area ratio (FAR). Although it might seem that the physical form and character of new buildings is highly regulated, the opposite is more often the case: physical character is often regulated loosely, if at all. In some communities, physical character is managed by design review boards or historic preservation commissions; in others, elected officials attempt to address it through negotiated zoning processes.

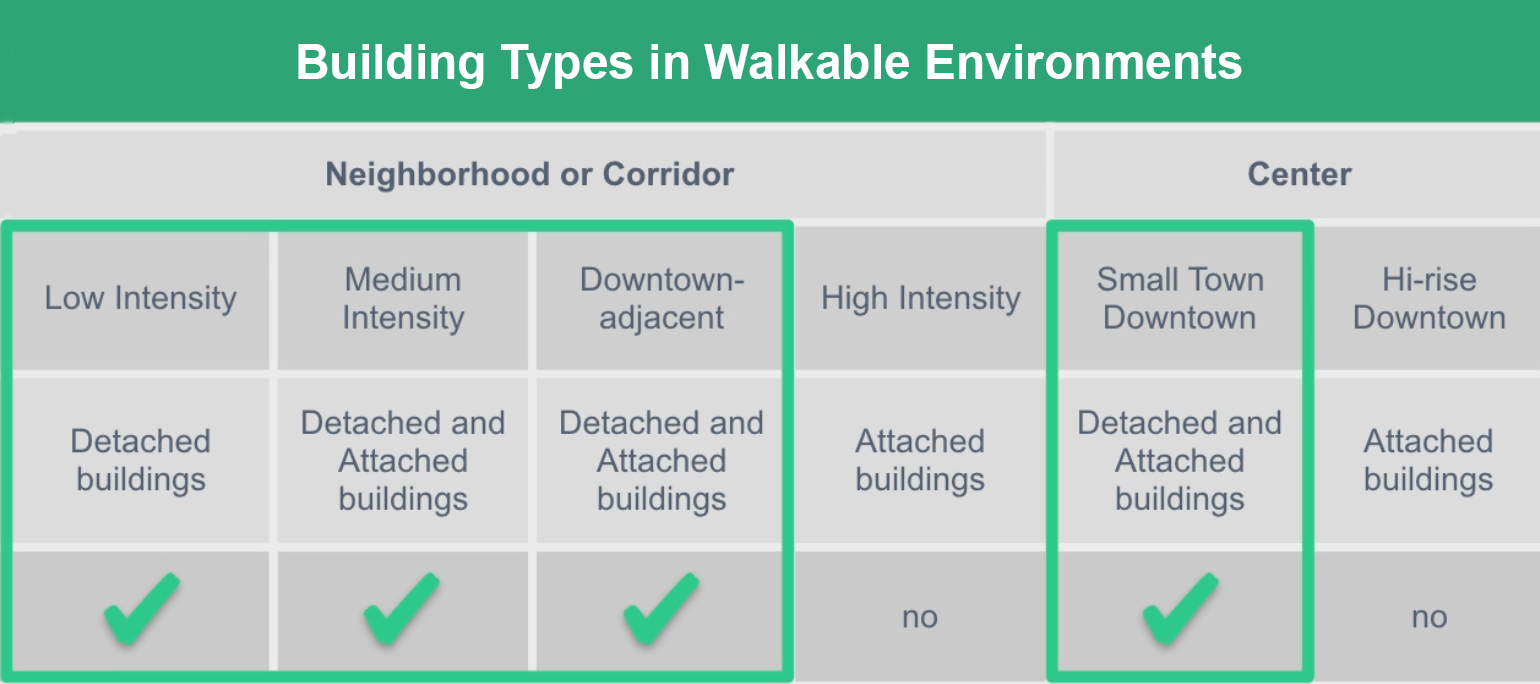

Form-based codes (FBC’s) are increasingly being used to supplement or replace ineffective zoning codes with more relevant and predictable regulations. Some FBC’s define specific building types as a regulatory technique. This technique can be either useful or counterproductive, depending on the physical context being regulated, as described in Part 2 of this series. For example, where the intended character is attached, large-footprint, or tall buildings, codes should focus on how the ground-floor facades interact with pedestrians. At this scale, building types can become an unnecessary layer of complexity in codes. At other ends of the urban spectrum, where the physical character is auto-dependent or where development occurs in ‘pods’ with a single building type in each pod, codes are also unlikely to benefit from including building types.

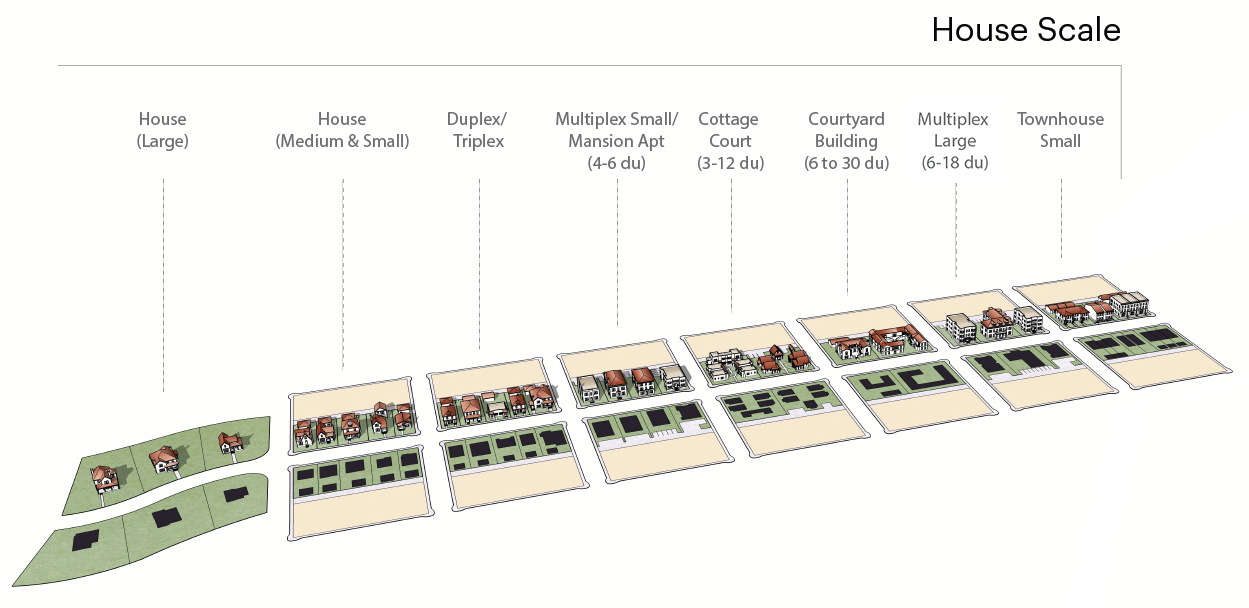

But when the intent is for mostly detached house-scale buildings with variety within each block, FBC’s can benefit by including building types. This is especially helpful in contexts ranging from detached houses to cottage courts, multiplexes, and courtyard apartments, and where neighborhoods are near main streets, offering a wider set of choices for making context-sensitive transitions. Well documented and clearly distinct building types help greatly in communicating. Think about asking a neighbor to envision a 1.14 FAR, 32 units per acre apartment building. Then think about asking them to envision a house-scale 4-plex. Which is more clear and communicates more effectively?

How building types change form-based codes

This article extends the previous discussions by focusing on HOW code writers can effectively apply building types in FBC’s.

Several portions of an FBC might not change at all when building types are included.

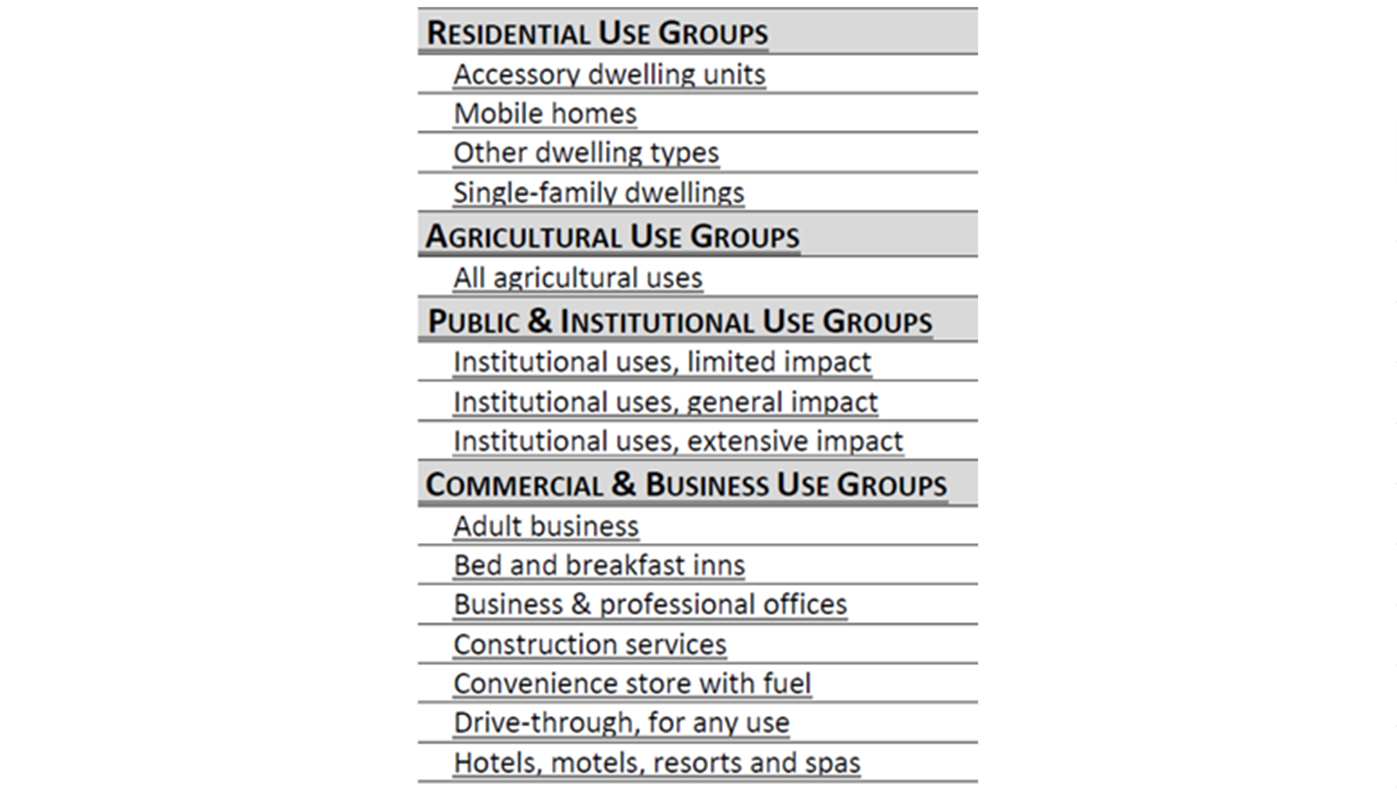

For instance, the simplified use matrix that determines the allowable uses of buildings can be used in codes that define building types. Since the same building type can accommodate different uses, the use matrix would not list individual building types. The allowable uses in the matrix would vary in some other manner, usually by specific geographic area .

Likewise, standards for street design, stormwater, civic spaces, or quantity of on-site parking would require little or no change if the code uses building types. However, for areas with smaller infill sites, the on-site parking needs to be coordinated with the physical context, the building footprint, and the proximity to services and transit.

Major changes to form-based codes

The most significant changes will be in the portions of the code that define building form and placement (which typically replace prior zoning rules concerning setbacks, density, and FAR). Another significant change can be in the regulating plan, in codes where the regulating plan specifies building types.

In order to determine how you might need to change your code to include building types, it’s helpful to understand the various approaches used in FBC’s to define building form and placement:

- Some codes replace conventional zoning districts with transect zones or other types of form-based zoning districts. This is a common approach when coding larger areas with varying character and intensity. These codes can establish a single set of standards for each zoning district (or for subdistricts within the new zoning district).

- Some codes provide more detailed regulations for individual blocks to implement a physical plan designed at that level of detail.

- Some codes allow developers to propose a specific plan for their property within a general framework established in an FBC.

- Some codes aren’t municipal regulations at all. These types of regulations are prepared for developers who will enforce them through restrictive covenants.

- Building types will be applied differently depending on the type of FBC. Some examples are described below.

Example #1: Developer codes

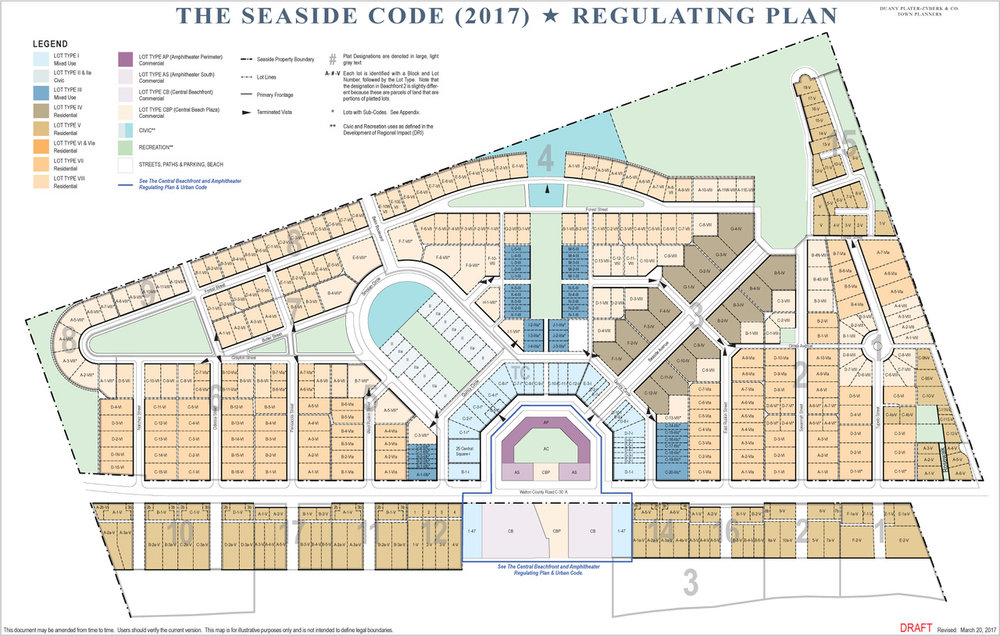

The iconic code for Seaside in Florida’s panhandle isn’t a municipal regulation at all. Developers can have greater authority than government over subsequent lot owners when they record restrictive covenants. That’s why the Seaside code was able to define eight building types and then specify only one of the eight possible building types for each lot in Seaside, as shown in the regulating plan for Seaside.1

The developer of Seaside implemented this code by employing a series of Town Architects who administered the code. They also created architectural standards during the early years while reviewing individual house designs. This coding approach, known as weak-code-strong-Town Architect, was later refined with clearer architectural standards and less discretion granted to future Town Architects.

Example #2: Municipal codes

Municipal regulations apply to thousands of individual lot owners and must comply with relevant state law and reflect constitutional protections such as due process and equal protection. When municipal FBC’s include building types, lot owners are generally allowed to choose from a selection of building types that are suitable for a defined area (unlike the single building type allowed under the Seaside code). One exception is where a municipal code establishes a series of allowable building types and requires developers to choose one type for each lot they will develop, with those choices being ratified by elected officials through a rezoning process.

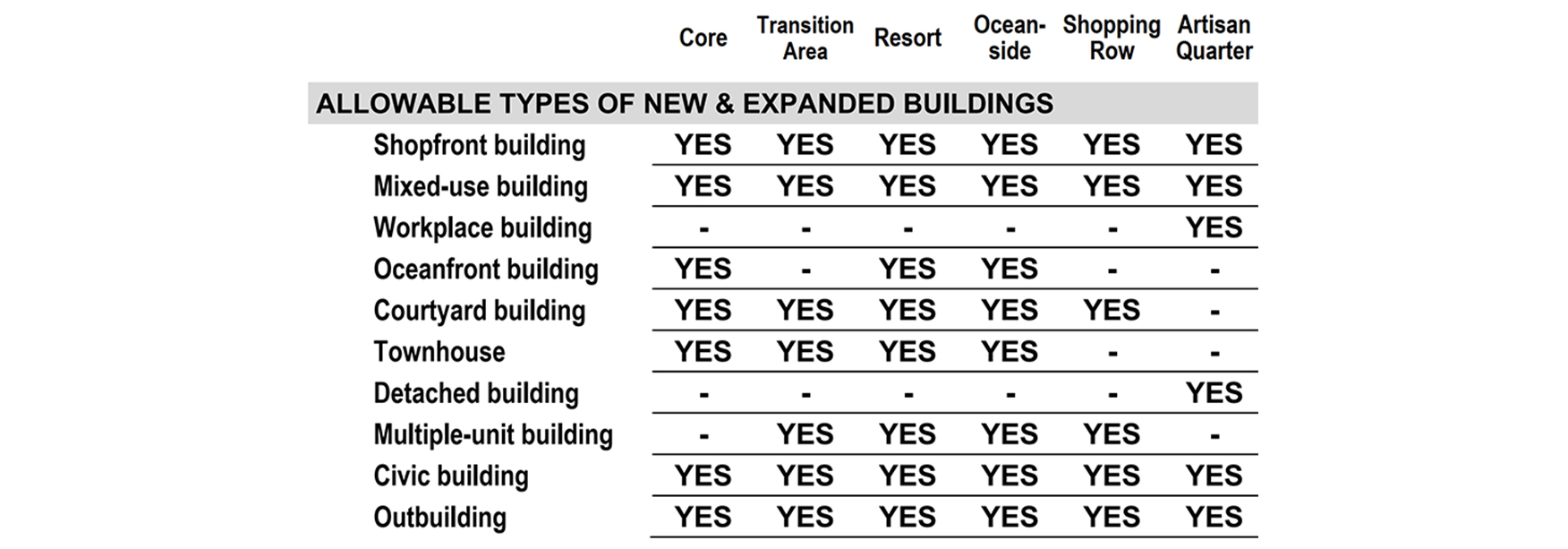

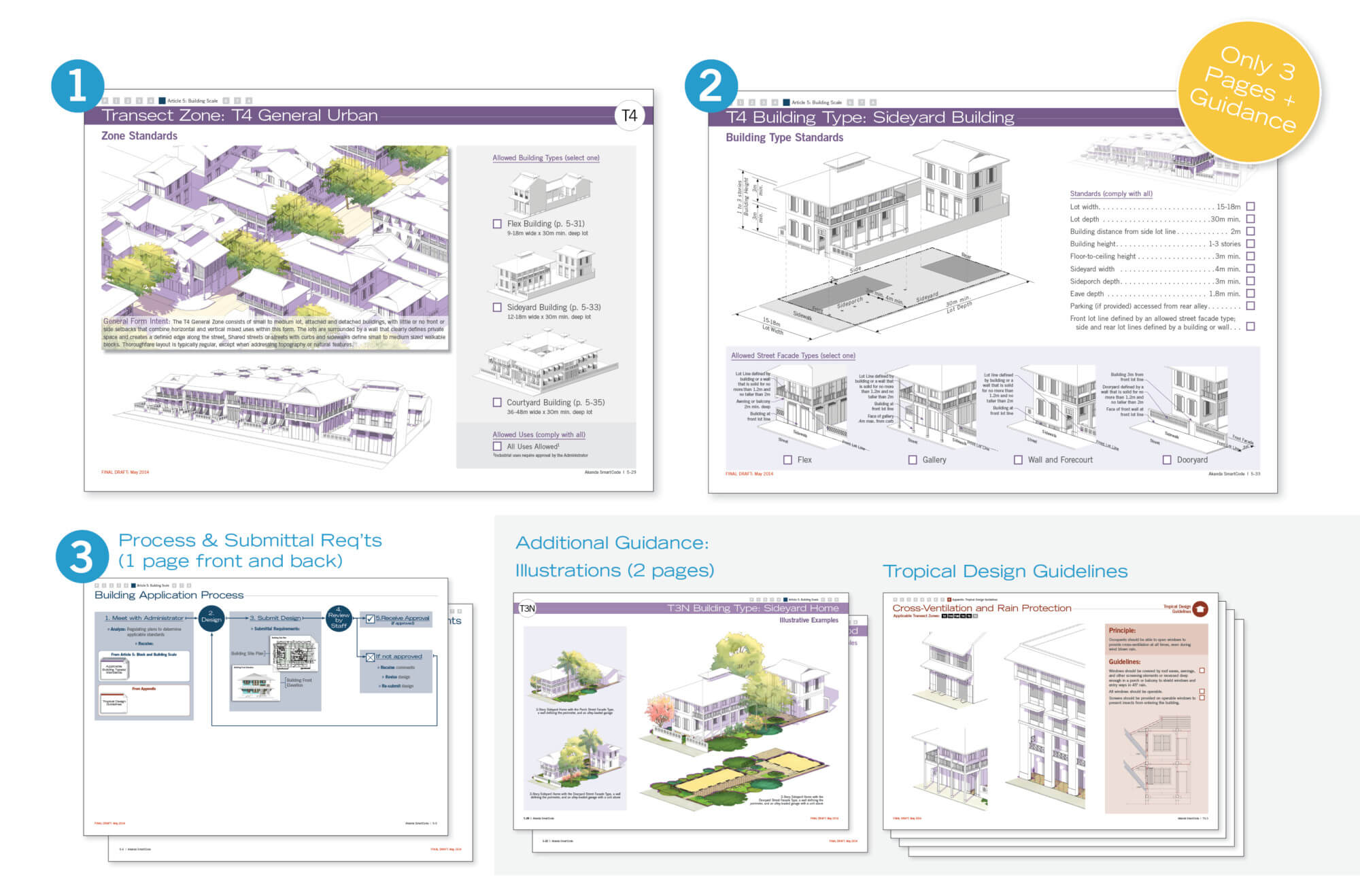

In codes that use building types, the regulating plans are occasionally specific as to building types as at Seaside. But most municipal codes don’t specify building types on their regulating plans. The regulating plans may designate transect zones or other zones of physical character and intensity, then assign certain building types to each zone to implement the intended form, as shown in the example below.2-5

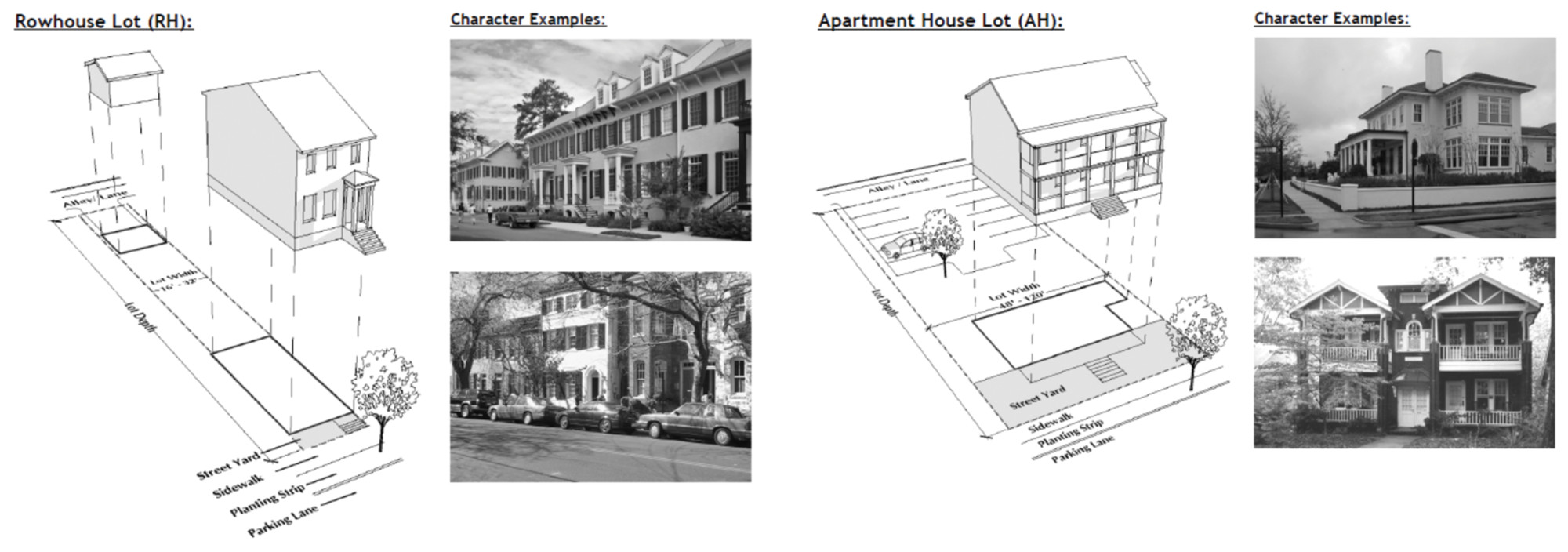

Codes can also assign a selection of allowable building types to designated street frontages. However, that type of code is most suited to areas of higher urban intensity, where most buildings are likely to be quite large or attached to adjoining buildings to form a continuous street wall. Building types are less useful in that context. They are more useful where buildings will have varied types and intensities, for instance in areas where side and rear yards will be common rather than rare.

Building form and placement

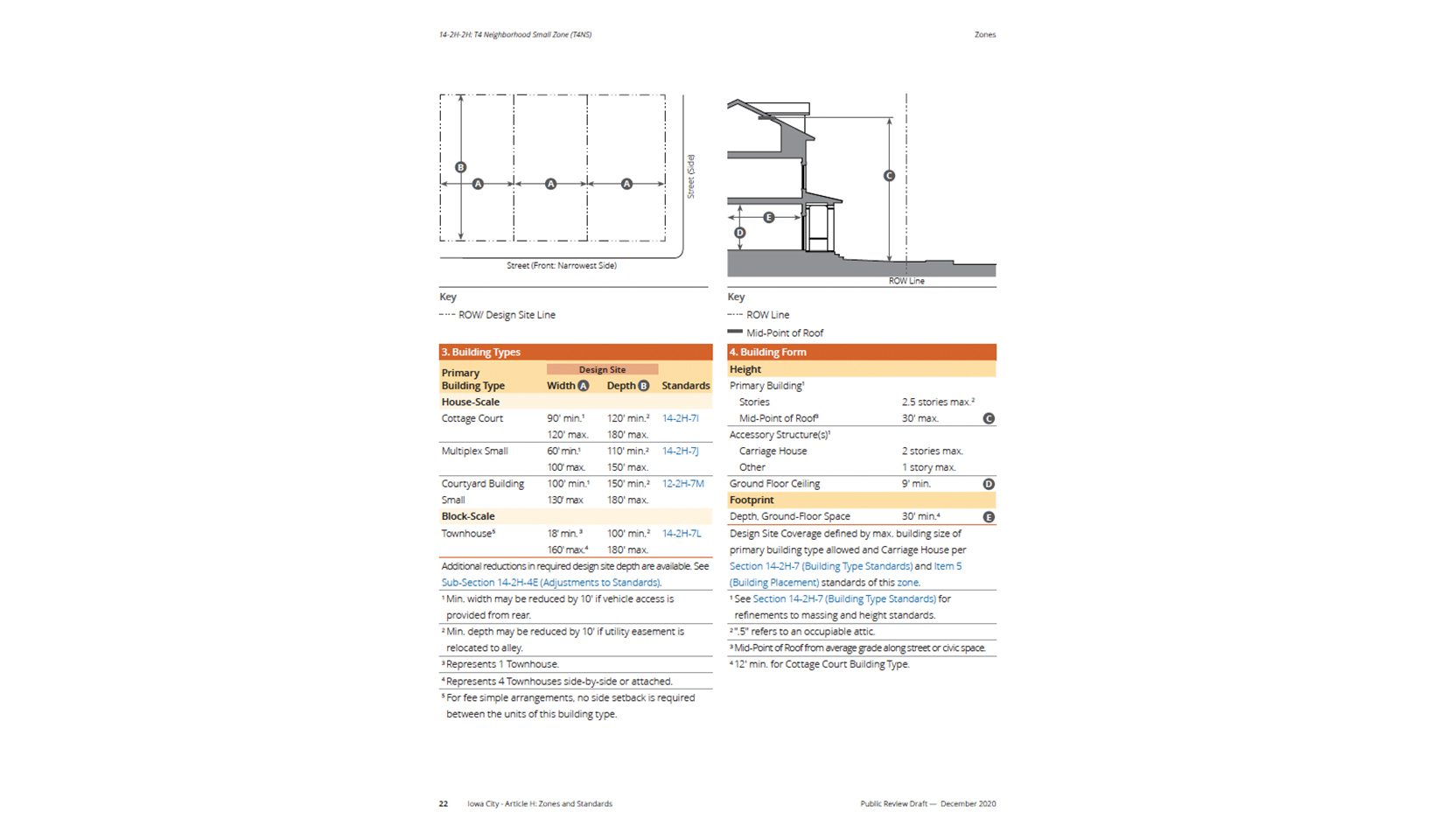

There are two primary approaches to specifying dimensional standards for building types in an FBC. Each building type can have a complete set of standards, such as the maximum building height, the required build-to line, side and rear building setbacks, location of parking, etc. Alternately, each building type might specify only those standards that differ from the general standards for the area where that building type is allowed.

These standards are often provided in a repeating graphical or tabular format that allows the built form to be visualized and allows the standards for each building type to be compared.

Diagrams that depict building types as shown in these examples are primarily illustrating the building envelope and the placement of the building on a lot. Such diagrams may also include windows, doors, sloped roofs, and other design features to show a typical example of each building type. If so, the code needs to be clear whether such features are design requirements or merely examples. If they are requirements, the rules must be spelled out in detail in another part of the code.

Common problems

The most common problem we observe with codes that include building types is when they are applied inappropriately, for instance to auto-dependent areas, or to intense urban areas where buildings form a continuous street wall and the main design issues are about overall height and how the ground floor facade shapes the public realm.

There are several other recurring problems:

Inconsistencies Between Building-type and Zone Standards. This occurs when the dimensional standards for building types conflict with other standards in the same code. For instance, when codes use transect or other form-based zones AND building types, the code must be clear as to which standards are established by the zone and which are by the building type (or which are modified by the building type). For instance, it would be acceptable to establish standards for the build-to line and the location of parking for each building type, while overall building height could vary by zone. This critical distinction needs to be clear to lay users of the code, not just to specialist planners or attorneys.

Lack of Coordination with Frontage Standards. Some FBC’s also include building frontage standards that apply to more than one building type (or more than one zone). As an example: a code might require front porches to be at least 8 feet deep and allow porches to be placed closer to the street than the building’s facade. It is essential that such regulations do not conflict with standards established for individual building types (or zones). The code should clearly indicate which standards are mandatory for all front porches (perhaps the depth of the porch), and which standards apply only to front porches that are placed closer to the street than allowed for the remainder of the building’s facade.

Lack of Coordination with Actual Lot Patterns. If the area being coded includes, for example, many small lots, building types need to be provided that can be built on those lots. Don’t require parcels to be combined to have enough area to make the Building Types possible. This is one of the most recurring problems and is usually the result of insufficient physical documentation of lot widths and depths and/or insufficient budget, or both.

Specifying Dimensional Standards that are Impractical to Achieve at that Location. Some codes provide dimensional standards that may be ideal under common circumstances but which have not been adjusted to the lot widths and depths of the area being coded. Again, this is usually the result of insufficient physical documentation or budget, or both.

Confusing Allowable Uses with Building Types. Building types accommodate the range of uses allowed by the zone with some exceptions of course. Yet, some codes identify building types as uses. This adds unnecessary complication to the code and misidentifies a physical object as a use.

Over-Identifying Building Types. While there are variations of the basic building types from region to region, it is not helpful to identify the variations if the essential difference is the name or some very subtle aspect (sometimes the type contains 5 instead of 4 units). Work to boil down the building types in the community to the ones that are clearly distinct in purpose, building size, and typical location. A related problem is when codes make distinctions between building types by their maximum allowed density. Often, these numerical limits are not tested on the very lots where the types are allowed.

Defining Building Types that are Not Integral Parts of Walkable Neighborhoods. Codes can provide standards (or design exceptions) for auto-dependent uses such gas stations or drive-through facilities on the edges of walkable neighborhoods, but such uses rarely require their own building types.

Conclusion

Codes that use building types are similar in most respects to other FBC’s. They differ, however, by providing either a full set of building form and placement standards for each building type, or by providing a limited set of standards for each building type that adjust or vary from general standards within the coded area (for instance, standards based on transect or other form-based zones).

Building types are most useful in FBC’s where the goal is enabling a fine-grained mix of primarily detached buildings of varied density and type in walkable environments. Within that physical context, coding details can vary considerably. When prepared well, building types facilitate and expedite the process of envisioning and achieving new buildings. Below we have illustrated the range of walkable environments most suitable for including buildings types in a form-based code.

About the authors

Tony Perez is a Senior Associate at Opticos Design, Inc.

Bill Spikowski is a Principal at Spikowski Planning Associates in Fort Meyers, FL.

References

- Code for Jensen Beach in Martin County, FL, prepared by Spikowski Planning Associates.

- Code for Seaside, Florida, prepared by Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company and revised by Michael Watkins Architect LLC

- Draft code for portions of Cocoa Beach, Florida, prepared by Dover Kohl & Partners & Spikowski Planning Associates

- Public Review Draft code for Iowa City, IA, prepared by Opticos Design, Inc.

- Code for Akanda in Gabon, Africa, prepared by Opticos Design, Inc.

- Planned Mixed-Use Infill code for Sarasota County, Florida, prepared by Dover Kohl & Partners & Spikowski Planning Associates