In each article, we cover each mistake one at a time, discuss why each is important to avoid, and provide graphic examples of both good and bad solutions, as well as even better approaches. This series is not meant to specifically call out certain cities, states, or efforts, but as constructive criticism designed to help more cities and states get it right. Missed the first article? Read our previous post to learn about MMH Mistake #1.

Missing Middle Mistake #4 - Not effectively regulating form and scale to ensure “house scale”

This form related mistake involves not effectively regulating the form and scale to ensure that buildings are house scale. A strong message that comes through in my book, that I now reinforce in my presentations and speaking events as well, is noting how easy it is to get caught up in regulating building height.

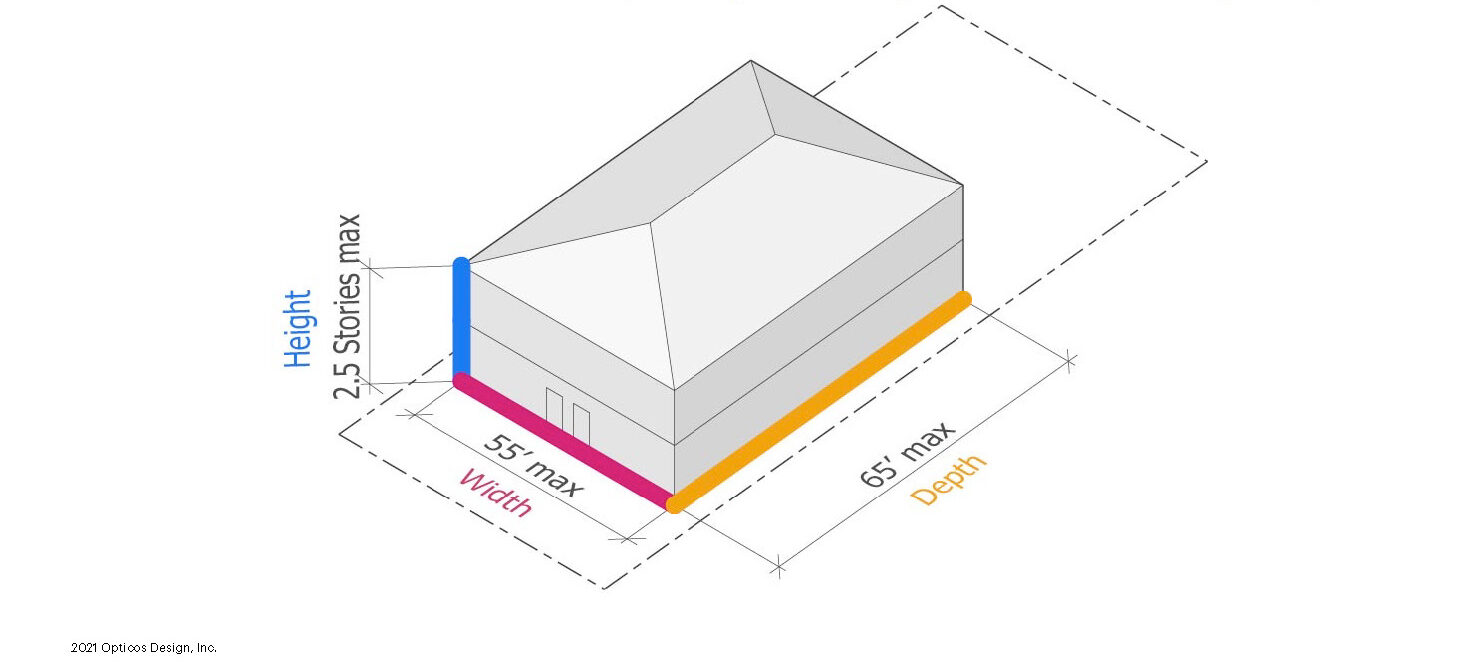

However, I am a strong proponent of building width and depth being just as important as height. We encourage cities and counties to regulate width and depth directly in their Missing Middle Housing efforts to better regulate maximum building footprint.

Why Regulate Maximum Building Depth vs Allowing Setbacks to Define It?

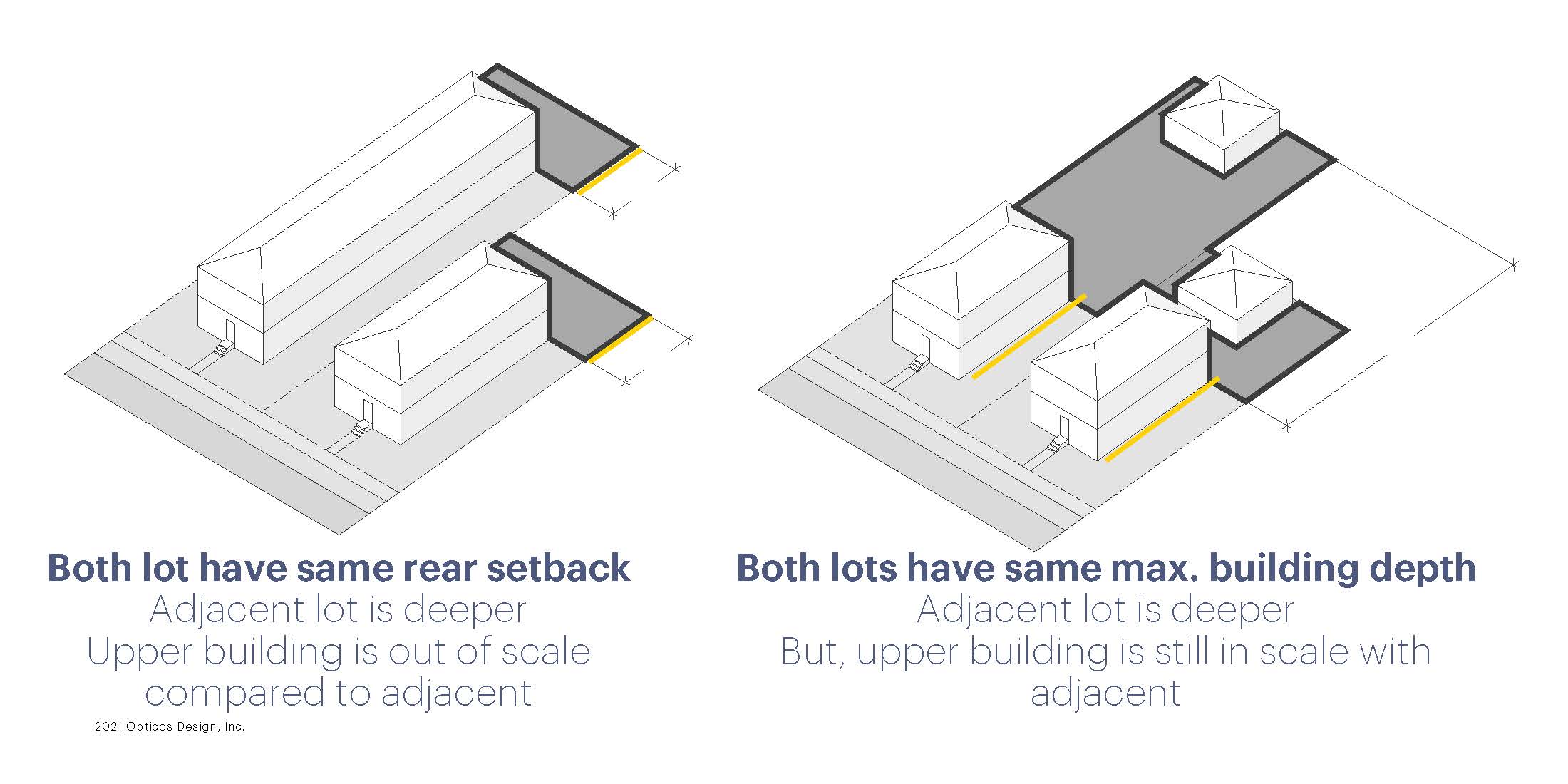

The question always comes up “Why would we regulate maximum building depth versus just allowing the setbacks to define that?” The number one reason I like to point out is that if all of your lots in a neighborhood are the exact same size, you might be able to ensure a predictable outcome, but in most neighborhoods there are exceptions to lot sizes.

This set of illustrations show that if you regulate by setting a rear setback (left), if that lot gets deeper you’re getting a much larger building that might be incompatible with the feel of the neighborhood. Whereas on the right, it shows that if you regulate by a maximum building depth, even if the lots get bigger it’s still delivering a predictable form.

So why regulate maximum building width versus letting the side setbacks regulate it? Once again, as the lots get wider, or if a developer is able to aggregate lots, it means they can deliver a much larger building that is not that house scale. At the point where a lot gets to a certain width, it allows for multiple buildings as opposed to allowing one large very wide building that might be beyond the intent.

This multiplex that I photographed in midtown of Sacramento is a great exception to the rule. It’s a corner lot that does fit well into its context. It has two stories and is a little bigger than we might typically define as house scale, but it is a really great exception that needs to be thought about as we’re writing our zoning codes.

It raises the question during the code writing processes as to whether a third floor should be allowed. We need to be very thoughtful about the impact of allowing a third floor, however the reality is that while you’re running pro-forma analysis to test the feasibility of the Missing Middle types you may need to enable a third story in order to really make it feasible; especially in higher value markets like the Bay Area. However, enabling a third story might have a broader impact as to how that building is perceived along the street so it’s important to be thoughtful about it.

To acknowledge this need for three and four stories, we classify them as Upper Missing Middle, a different classification than regular Missing Middle. We have created a unique zoning district to enable the core Missing Middle types at house scale and it’s likely that you would have another zoning district to allow for Upper Missing Middle. This helps clarify the conversation about where which types are going to be enabled.

Continue reading our MMH Mistakes series to discover MMH Mistake #5 Not effectively addressing parking requirements as a barrier.

Are you interested in implementing Missing Middle Housing types in your city or town? One of the first steps we encourage you to take is to complete an MMH Scan™. This service identifies where a city should prioritize Missing Middle applications and identifies the specific barriers to implementation. It’s a significant first step that can inform a comprehensive plan. Contact us to learn more.