Zoning Isn’t New

I have met many people across the country who were unaware of zoning and that it has been regulating their property for the past century. It’s not that they didn’t know there were rules in place—it’s more that they couldn’t have told you what actually regulated building or land use activity in their area. Many people realize that zoning exists when they need to get a permit for a particular home improvement. This is may be difficult to imagine in highly regulated areas, but it’s not uncommon.

In the United States, zoning laws have been in place since the late 1890s. These initial laws were aimed at specific issues related to the height of very large buildings and the effects on neighboring property. By the 1920s many communities had begun to use zoning to address a wider variety of issues—most notably, health-related issues between industrial and residential properties.

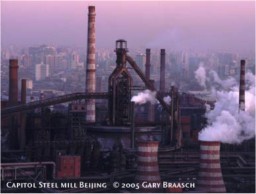

Before such laws were established, factories could operate as they wished and even move in to a residential area. Businesses could conduct their activities without worrying about it affected nearby residents or other businesses. Similarly, residential buildings were often built without considering what would help or hinder the lives of the tenants or their neighbors. In short, growth and expansion within communities was seen as independent of needing to consider how one person’s new investment affected the existing investments of others.

“Growth and expansion within communities was seen as independent of needing to consider how one person’s new investment affected the existing investments of others.”

For nearly a century, public zoning laws have ensured that property owners can rely on stable, valuable property, although, some owners have opposed zoning because it restricts their ability to use their land or because they feel it makes it harder to sell. It’s interesting to note that zoning often contributes to a property retaining its value precisely because owners and potential investors know how adjacent and nearby properties can be used. While some perceive zoning as a limiting factor, others see that it provides stability for their investments. For further illustration, spend time in a country where anyone can build or operate as they wish, where and when they wish. Knowing that nothing—you name it—is out of the realm of possibility should get your attention.

For nearly a century, public zoning laws have ensured that property owners can rely on stable, valuable property, although, some owners have opposed zoning because it restricts their ability to use their land or because they feel it makes it harder to sell. It’s interesting to note that zoning often contributes to a property retaining its value precisely because owners and potential investors know how adjacent and nearby properties can be used. While some perceive zoning as a limiting factor, others see that it provides stability for their investments. For further illustration, spend time in a country where anyone can build or operate as they wish, where and when they wish. Knowing that nothing—you name it—is out of the realm of possibility should get your attention.

Great Places Built Without Zoning

Over the past 50 years, the effectiveness of zoning has generally decreased while its presence has increased. The immediate purpose of early zoning laws has faded into a necessity that has become confused about its purpose and its true benefits. Many of the places our society values the most were built prior to the existence of zoning codes. Such towns and neighborhoods were built as economic investments but with a clear understanding that these places were composed of coordinated and arranged physical elements: If these elements were not balanced and arranged carefully, the results might not promote the desired investment.

Streets and streetscapes were coordinated and designed with the houses and the shops that fronted them. The houses and front yards on one side of a street were coordinated and designed with those on the other side. The street network was laid out to make it enjoyable to walk along them and to view civic buildings. Certainly, urban design—the art and technique of laying out neighborhoods and towns—varies from culture to culture, but the technique of urban design is far older than zoning laws. So on the one hand, there was a strong record of making great places without needing rules for how to make them, but on the other hand, there was nothing to prevent the incompatibilities presented by the industrial revolution or by people who didn’t value the places or their neighbors.

Use-Based Zoning

Zoning laws were introduced in response to the incompatibilities that resulted from the lack of good rules about urban design. The rules were primarily health-related. Zoning was responding to very serious issues that affected how people breathed and what they had to endure as neighbors—situations that today wouldn’t be tolerated for an afternoon. As a result, zoning’s original focus and perspective was activity. Instead of evaluating the combination of factors and physical components involved in an incompatibility, the activity itself became the factor that received the most attention. Initial solutions focused on separating certain activities from others—a reasonable but incomplete approach. This focus gave rise to the term “land use.” Land use was, and continues to be, important, but because of this limited focus, the zoning system became myopic, launching a trend that ignored the physical realities and complexities of communities.

The result was that towns and neighborhoods were separated from their constituent parts. Imagine needing to respond to a complex system such as the human body with a set of tools that only recognized a small percentage of the body’s parts or functions— that’s exactly what happened in many cities and neighborhoods and continues to happen today. Zoning laws became and continue to be extensive on land use activity, but trivial or silent on the other 90% of what makes up the community.

If you’re wondering how cities and neighborhoods could have “physical complexity” or why that’s important, take a look at what we call “cookie-cutter” neighborhoods—such places lack complexity. Sure, there are plenty of places made up of very similar buildings that are complex. The reason that complexity exists in such a place is because the buildings or “background”—while repetitive—are within a pattern that stimulates a wide variety of activities. Places that do not stimulate a wide variety of activities are considered less appealing. Highly desired places are not necessarily fancy, but are beautiful because of their inherent variety, arrangement, and physical complexity of their parts. Less desirable places either never had such variety, arrangement, and complexity, or have lost it due to new investment that has disrupted that pattern.

“If you’re wondering how cities and neighborhoods could have “physical complexity” or why that’s important, take a look at what we call “cookie-cutter” neighborhoods.”

Zoning that is still focused primarily on land use activity often frustrates rather than enhances investment. This is generally because the previously clear purpose of separating incompatibilities has been increasingly stretched to the point that in many communities, zoning itself has become irrelevant to the very property and improvements it was intended to serve. As a former public sector city planner, I recall working with such zoning ordinances in a number of communities. It’s interesting and unsettling to note that as zoning was copied from one community to another in the 1940s and 1950s, many communities unintentionally erased the uniqueness that each community had previously possessed.

In the process of applying use-based zoning, areas of town that were still thriving came to be seen as “non-conforming.” The zoning system was forcing existing places—great places—to conform to abstract regulations that were often not aware of the place they were regulating. Amazing but unfortunately true, and not a thing of the past. It’s one thing to choose another way of developing new areas of your community but quite another to render existing neighborhoods and main streets essentially illegal to rebuild. That’s the effect that use-based zoning had and still has in many communities. Typically, everything goes along fine until a community suffers a disaster and discovers that its zoning laws will not allow a really nice neighborhood to be rebuilt.

Use-Based Zoning Out of Sync With the Community

As a member of city staff, I attended meetings with community members to discuss ideas acceptable to the community. Yet, many ideas were not possible under their use-based zoning. I often had to tell people that their well-intended and logical vision for a particular area of town wasn’t allowed by existing zoning. Often, these were laws were younger than the people who had lived there all their lives, in desirable areas now deemed illegal.

So, in looking at what to do about this, I’ve had to talk with many communities about how their zoning system was never really aware of or able to recognize the built environment it had been regulating. Even though communities know a lot about what they don’t want in their community, use-based zoning leaves them with few answers about what they do want. While zoning had become obsessed with land use, other equally important aspects of a community went largely unchecked. This is not a preferred position for a community that values its future.

“Communities know a lot about what they don’t want in their community, but use-based zoning leaves them with few answers about what they do want.”

When people saw that land use wasn’t everything, they started looking for ways to protect their neighborhoods and cities. But by that time, a real understanding of the built environment had grown so far apart from the zoning system that the choice was left to the investors or those with the time to voice their opinions on a development project. This approach resulted in processes that were meeting heavy, wearing out the participants and generating weak content. Many communities spent a lot of time just to apply an interpretive set of policy directions called design guidelines.

When people saw that land use wasn’t everything, they started looking for ways to protect their neighborhoods and cities. But by that time, a real understanding of the built environment had grown so far apart from the zoning system that the choice was left to the investors or those with the time to voice their opinions on a development project. This approach resulted in processes that were meeting heavy, wearing out the participants and generating weak content. Many communities spent a lot of time just to apply an interpretive set of policy directions called design guidelines.

The design-guideline approach deals with the wide range of information missing from most zoning ordinances. The generally weak understanding about what actually makes up a community, such as its open space, neighborhoods, centers, districts, corridors, blocks, streets and streetscapes, buildings, signage, and land use, is carried forward into the structure and content of design guidelines. It’s not uncommon to find guidelines that really don’t do much more than the use-based zoning they’re intended to clarify. Further, because guidelines are policy and not standards, the challenge becomes to articulate enough “guidance” without conflicting with the actual requirements or stifling creativity.

While design guidelines tend to be a weak tool in general, I have read excellent design guidelines across the country. The common factor among these examples is that their authors recognize the variety of parts that make up a community. In my experience however, the majority of design guidelines do not recognize the latent physical structure of a community and tend to compound the problem rather than help, adding yet another layer of information that needs to be interpreted on a daily basis.

Form-Based Zoning

Because zoning does offer a number of benefits, Form-Based Zoning was developed as an alternative to the system of use-based zoning and design guidelines.

Form-Based Zoning recognizes the components of the specific community it would regulate, not those of another place, and focuses on the physical form of a community, while understanding that the community is a long-term investment that will see many changes over its lifetime. Form-Based Zoning addresses land-use activity, but with less detail on the specific businesses that should be allowed in a particular building, by identifying the range of physical realities expected to continue or be built where nothing exists. The form-based system can recognize each part of a community as a component with its own “settings” based on location, providing owners, residents, and businesses with information and options for reinvestment that are integrated and compatible for each area of town. This approach involves more questions than the use-based approach. But the answers are not unattainable. It only requires conducting clear discussions about what people want and do not want within a structure and language to recognize the parts of their community. The form-based approach lets people see and adjust the actual components that are contributing to what they like and also lets them understand why they don’t like something. It’s a far more effective way to protect and promote investment and improvements in a community.

Form-Based Zoning Responds to Community Needs and Priorities

In contrast to use-based zoning, Form-Based Zoning is modular and scalable to an area of a community or to an entire city. It is a system that acknowledges as many or as few topics as desired by the community. As discussed above, the topics are the physical components and land use activities that make up the community. Because Form-Based Zoning is a system that responds directly to the components that it regulates, the level of information and requirements for the same component can be adjusted for different priorities and locations. For example, in historic areas with a strong physical character that people want to preserve, Form-Based Zoning responds with a wider set of tools and more settings. Those tools and settings have a direct purpose: Keep what is already great about the place and make each new investment contribute in precise ways that are compatible for that place.

However, in the same community, there may be areas where the priority is more about directing investment in a general pattern with less concern for details and high quality aesthetics. In these areas, Form-Based Zoning responds with a shorter list of tools and settings. For example, the settings for shopfronts and streetscapes on your beautiful main street are probably going to be expecting far more than the settings for shopfronts and streetscapes on an average corridor in your town. The same component is used, but adjusted for priorities based on location. In this way, the various areas of a community can “dial up” or “dial down” the requirements depending upon the priorities of a location. Form-Based Codes can be as detailed or as simple as you want them to be because of their direct relationship to the built environment they serve.

“Form-Based Zoning tools have a direct purpose: Keep what is already great about the place and make each new investment contribute in precise ways that are compatible for that place.”

Increasingly, communities are recognizing that their use-based zoning isn’t entirely responsive to their needs. It isn’t intentionally negative; it’s just incomplete. More communities, large and small, are changing their entire zoning system to a form-based system.

Most communities identify areas where Form-Based Zoning can help without changing all their zoning. This approach allows communities to keep use-based zoning for areas that are not likely to change or see development pressure in the next 25 years or so. Areas under development pressure or where change is highly desired are targeted for Form-Based Zoning. Also, because Form-Based Zoning is modular, some communities test the approach by applying form-based standards for a minimal set of topics in a single area of town with a more expansive set of topics in other areas. A key question to ask when considering Form-Based Zoning is: Do the current standards in your community consistently deliver the community vision or not? If the answer is yes, then that’s great news—and keep up the good work. If the answer is maybe or clearly no, then it is worth exploring what amount of Form-Based Zoning you need and for what purpose.

I have worked on a total of 42 Form-Based Codes and code frameworks for a wide variety of situations and communities through my career. I believe that this technique of zoning, despite its somewhat awkward label, continues to improve in its content and execution. Nothing is perfect, but I find Form-Based Zoning to be a more effective and responsive tool because it gives clear and consistent information, protects property and its value, and contributes to the stability and enhancement that most people want in their communities.

I look forward to discussing this with you.