Form-Based Coding is a key tool to unlocking walkability, but we’ve found simply having empathy for all parties at the table can be paramount. While almost always interested in building the long-term value of a community, administrative staff may be facing certain political pressures in the present. At the other end of the room, developers are often focused more on a near-term gain than long-term assets(1). Working through design alternatives that positively impact both of these interests can be challenging.

A rule of thumb? To get walkable places, advocates of good urbanism have to answer “What’s the value to me?” for both developers and the public. Here are some of the top discussion points we’ve seen gain traction with both “sides” of the urban design discussion.

Walkability

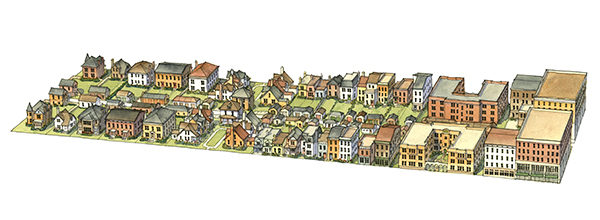

What Is It? Having amenities and jobs close to housing; building activity geared to the public realm; a physical environment that’s nice to be in, not just pass through

Developer Value: Walkability adds long-term value by catering to the 50% of the population that considers being able to walk to daily goods and services a high priority. Near-term value is gained through narrower streets in well-connected networks by generating better access to the lot and adjacent lots, reducing traffic speeds, reducing stormwater runoff and reducing cost for construction and maintenance. Reductions in traffic speed can potentially increase adjacent residential property values. Long-term value is gained through the ability of such a network to be able to adapt more easily to unexpected market shifts.

Public Value: An interconnected network of streets with pedestrian-oriented characteristics adds long-term value by creating a better balance of land uses and economic generators. Narrower streets in well-connected networks decrease accident rates, facilitate mobility choice, and enable the reduction of vehicular miles traveled.

Quality Building Fabric

What Is It? Buildings with character-rich and thoughtful design

Developer Value: Beautiful architecture adds near- and long-term value by offering product that looks good, ages well over time, and contributes to the brand of the place—the result of durable materials, pedestrian interest elements (i.e. doors, windows, frontages, balconies, human-scale signage, etc.) and human-scale lighting.

Public Value: Pulling buildings up to the street and placing parking in the rear adds long-term value by physically defining streets and open spaces, inviting reinvestment over time. A building fabric that lasts beyond one building cycle also contributes to reinvestment by being able to adapt to changing market cycles.

Open Space and Trails

What Is It? Parks and natural areas with people-focused connections

Developer Value: Public gathering spaces physically defined by community-focused buildings add long-term value. Well-distributed public open spaces and trails create near-term value—properties within short distances of open space have shown clear premiums.

Public Value: Open space creates what community developer Bill Gietema calls an “emotional center of gravity,” and it generates opportunities for active and passive recreation. Providing a range of communal open space types and sizes that focuses on quality versus quantity is also critical for smaller housing types that lack a big yard. Many American households today consist of older “empty nesters” and millennials who are putting off traditional marriage, most of whom desire housing that requires less maintenance (i.e. little to no yard) and is within a short walking distance of amenities.

Frontages

What Is It? The way the building meets the public realm

Developer Value: Properties gain long-term value by having porches, stoops, dooryards, terraces and galleries that are a usable depth and have direct access to the sidewalk. Rental premiums from outdoor living space and spaces for dogs create near-term value.

Public Value: Usable, permeable frontages activate the street, adding long-term value with open sightlines and visual interest. Porches, stoops, dooryards, terraces, galleries and balconies enhance the sense of community by providing opportunities for citizens to socialize in a safe, walkable environment.

Variety of Housing Types

What Is It? Different forms of housing—from single-family homes to Missing Middle Housing to context-appropriate mid-rises and high-rises—of varying prices

Developer Value: More housing options create long-term value by providing a mix of residential product types that address multiple market niches. A clear case of this was observed during the 2008 housing market collapse. The value of housing stock in monoculture subdivisions went down at one time; however, in walkable, urban areas the collapse had only some impact because of the diverse variety of product offered. As we have seen through our Missing Middle Housing research, near-term value is gained through high market demand for smaller, well-designed homes within a walkable context.

Public Value: More housing choice adds long-term value by allowing residents the ability to age in place and retain social capital, which is important for the evolution of sustainable communities. People living in walkable neighborhoods trust their neighbors more, participate in community projects and volunteer more than those who live in non-walkable areas. A strategic mix of residential product types also attracts people to move to the community, both for variety and what that variety generates on nearby corridors (i.e. services, restaurants, transit, etc.).

Empathy by Experience

Through any urban design discussion—even the most technical of debates—it’s above all else important to understand the interests of those at the table. This is not an exaggeration—it’s something I have gleaned from my own experience as Urban Design Officer (UDO) for cities directly (Rowlett and Fairview, Texas); in countless initial/long-term value and UDO conversations with Dennis Wilson at my previous firm, Townscape, Inc.; and from knowledgeable community builder colleagues I have leaned on to gain perspective. As liaisons in planning and development discussions, urban designers must appreciate both sides.

(1) More on this concept can be found in the New Urbanism Best Practices Guide, “Investing in New Neighborhoods,” p. 236