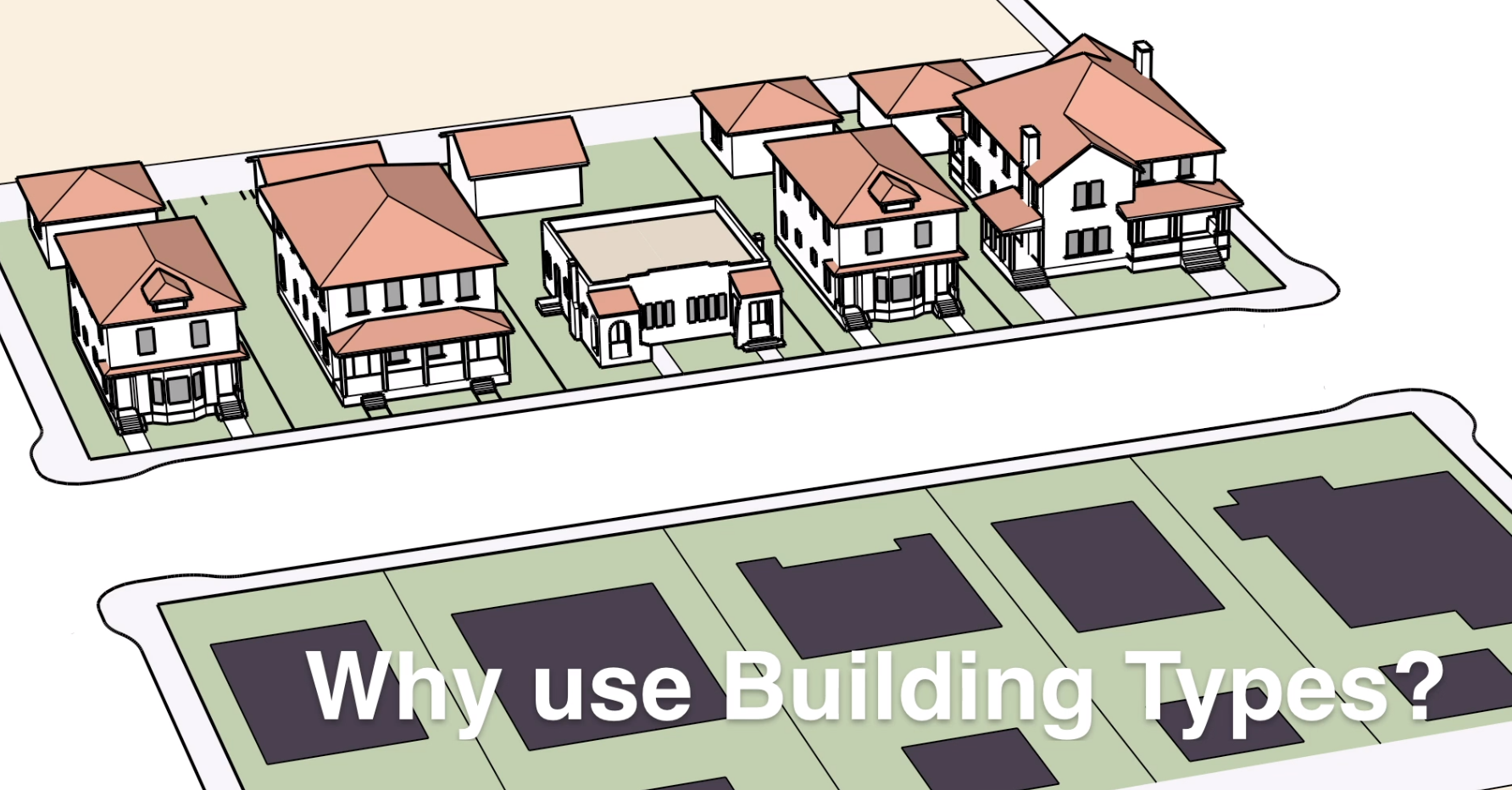

The diverse palette of ten to twenty building types that made many walkable places was effectively reduced to three general choices: single-family houses, mid-rise to high-rise apartments, and civic/commercial/industrial buildings. Further, the variety and distinctions between each of the building types were seen as irrelevant for zoning, dismissed as “design details” by many.

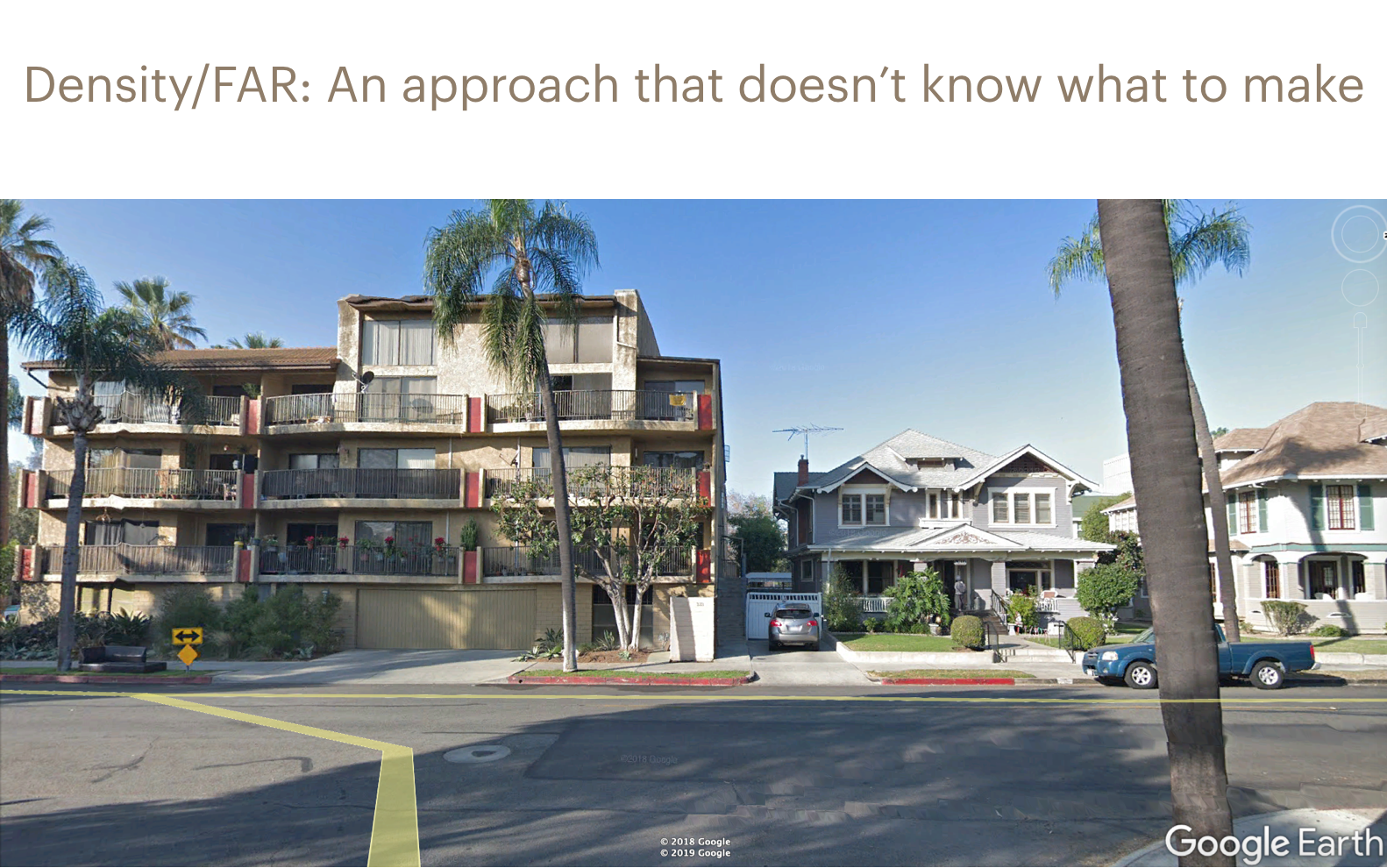

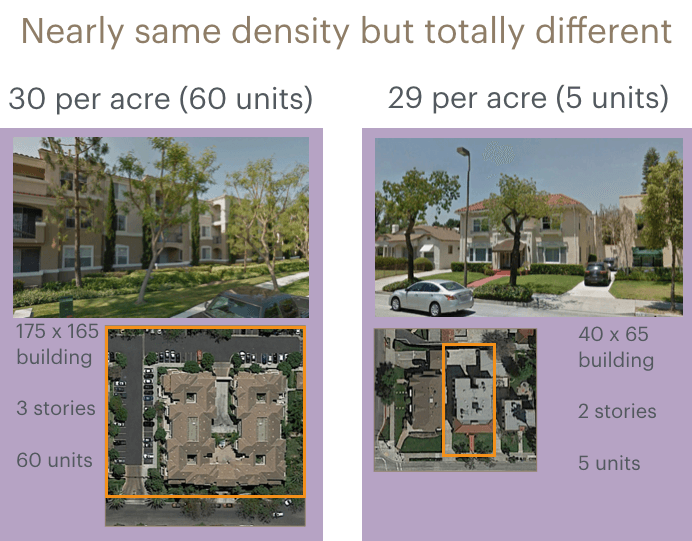

Building types and their ability to respond to specific, local needs were discarded for a numerical system about quantity and bulk featuring quick density and FAR calculations. With the new system, anyone could now produce an easy numerical answer about total square footage. Certainly, a common and important question. But was that worth the blunt system of density and FAR that we received in exchange? Easy calculations and a ‘simpler’ system were favored over a long track record of building types being artfully and responsively making all types of neighborhoods, centers, and cities. As evidence of how this adversely affected place-making, many zoning codes include the term ‘bulk’ and typically address it as something negative, something to mitigate. The sophistication of building types was reduced to discussions about quantity. And suddenly, that was now something to be tamed. Interestingly, it’s the system of density and FAR that caused the unpredictability in physical form that justified zoning’s need to mitigate building bulk.

After about 60 years of that experiment, many communities are changing their approach in favor of Form-based codes (FBC’s) to return the primary focus to physical character. Along with this change, building types have regained attention, being a key component in the original FBC’s over 30 years ago and in many recent FBC’s. Yet, among code practitioners and public sector planners, there is significant disagreement about the effectiveness of and need for building types. Some say it’s too confusing and not necessary. Some say it’s just another thing to deal with in an already complicated process. Some say they’re indispensable.

In looking closer, it’s not an all or nothing question. It’s about where. For example, where the intended physical character is mostly attached, large footprint or tall buildings, the real question is how the ground floor facades are to be designed for pedestrian interaction and possibly some massing stepbacks to consider if there’s existing historic character. In these situations, building types aren’t needed. Also, where the intended physical character is auto-dependent and variety is at the scale of development pods where each ‘product’ is in its own pod, building types aren’t needed. But when the intent is for mostly detached house-scale buildings and variety within each block, building types are very helpful. In these situations, you can select certain building types for the ends of blocks along busier streets and other types for further into the neighborhood where expectations are for more distance between buildings and more privacy. This approach lets everyone see what their choice means in terms of size and intensity on a lot that fits in their neighborhood. Sure, communities already address this through setbacks, density, FAR, and other limitations, but it’s easier, more understandable, and accurate with building types.

This question of where to use building types is an important one that doesn’t get the attention it needs. It’s usually at the level of whether or not to include them. Most of the time, the answer is categorical: yes or no. This approach has led to either not applying building types at all or, in applying them across the entire code boundaries without questioning if that’s really appropriate. This lack of critical thinking to see where they do and do not make sense is partly due to inexperience by some code practitioners. I certainly made that mistake in my early code writing. It’s also partly due to the reality that applying building types takes more upfront work and coordination. When faced with a tight budget, some communities have included an over-simplified version of building types that doesn’t provide helpful information and direction. This approach has resulted in some codes that are confusing, cumbersome to use, and ineffective. This reinforces the skeptic’s view of building types and confuses those that are interested.

In our work across the U.S., we see a need for what building types offer: predictability about scale, footprint, and fitting really well into an established or desired neighborhood pattern. Combine this need with the reality that most zoning codes and design guidelines don’t have enough useful information to help make buildings fit their context and make good neighbors. Most address the issues through committee review and multiple iterations, costing time and money while not usually resulting in a predictable or desired outcome. In addition, zoning standards and guidelines often include lots of photos and words about good design but then apply general height standards, or density and FAR limits that don’t recognize the realities and needs of different sizes of buildings.

In looking closer, it’s not an all or nothing question. It’s about where.

However, through a well prepared building type approach, your zoning can directly address key issues like building scale, footprint, height, massing, on-site open space and parking on the terms of each building type and its specific context. For example, how a fourplex uses on-site open space is completely different from how a courtyard building uses it. By the way, both of these buildings are house-scale types. Can your code tell the difference or does it treat both buildings the same? A well-prepared building type set of standards can see these differences because it sees each type, its needs, and where and how it can fit well with other buildings. In contrast, the density and FAR approach only sees bulk and basically treats all non-single family development alike. Building types enable your standards to be customized for each type while fitting it all into the neighborhood’s physical character and making your zoning realistic and responsive. This has become especially important in states like California where the legislature is demanding objective design standards because communities have made the process unclear, lengthy, and slow to produce seriously needed housing. We encourage you to consider building types where they make sense.

Read part 2 for more on where to use these building types:

Check out our course at Planetizen.com