As David Walters so accurately describes in his recent blog post, people and real places nationwide have had to adjust themselves to the unclear and inconsistent tool that is conventional or “use-based” zoning. Because of the inability of this zoning to recognize real and appealing places, all sorts of experts have developed to interpret the tool instead of replacing it.

When something challenges the status quo, the challenge either quickly fades, or it exposes weaknesses and offers a viable alternative. When form-based zoning exposed the weaknesses of use-based zoning, there was shock that such arcane and irrelevant systems are still in operation. These systems do not really serve people or property as zoning should. Walters’ reminder about the massive gap between what zoning does and what zoning needs to do should motivate people from all perspectives to demand more—lots more—from the zoning that regulates their property.

In support of Walters’ request for more clarity and connection between zoning and the very places that it regulates—and in order to highlight our observed best practices in form-based zoning—we offer the following.

Instead of “Mixed Use,” Say What It Is

As a planning term, “mixed use” can have muddled connotations. We agree that the “alphabet soup” of conventional, use-based zoning—use of complex and abstruse letter- and number-based designation systems—doesn’t help at all. However, we have found that the “mixed use” term has also become muddled—it means many different things to many people. Unfortunately, the term is easily misused and further confuses. We recommend that everything be considered mixed, to a degree: very little or entirely. The degree and intensity of mixing are the important factors. For example, a small shop at a crossroads with one caretaker apartment behind or above the shop is “mixed use.” So is a house in a neighborhood that has music lessons a few times a week in the backyard garage. So is the building the size of a block with lots of ground floor shops and a few upper stories of offices or apartments. The same goes for an entire downtown of these buildings. Some argue that a shopping center with a bank, a few professional offices and drive-thru restaurants is “mixed use.” Even if you don’t accept the last example, the others each have very different physical characteristics. Yet, they’re all “mixed use.” And they’re all “centers” on a spectrum.

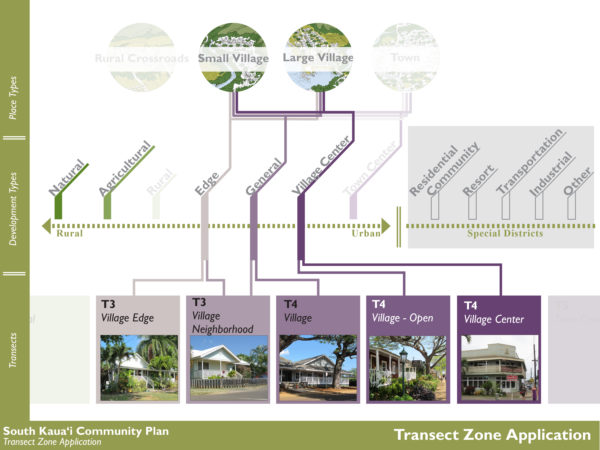

Instead, recognize that there are multiple mixed-use Place Types, and identify them with more descriptive names, such as: “crossroads,” “neighborhood,” “main street,” or “downtown.” There are varieties of each, and you can use other factors to further distinguish them.

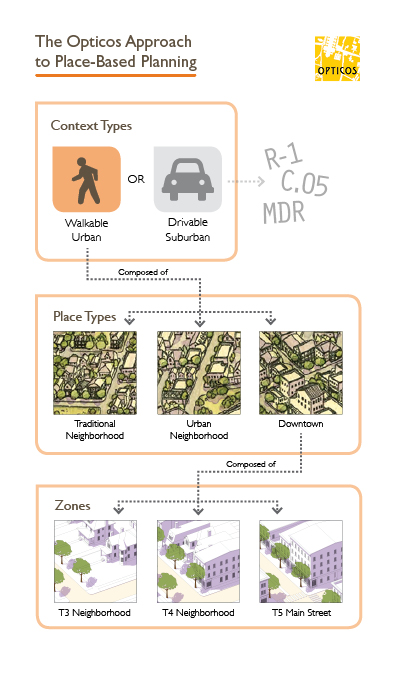

Place Types are a Combination of Zones

In his article, Walters mentions Place Types, which are the “basic building blocks of urbanism.” This is a very powerful tool to understand and plan the future of a small town, city, and region alike. However, there is a nuance to make clear: In our experience, a Place Type is the combination of several environments or “zones”—not just one, as Walters alludes to. For example, a downtown typically has two to three distinct environments, yet it is seen and functions in the greater whole as one Place Type.

Similarly, a walkable neighborhood typically has at least two environments: the areas that are mostly single-family houses and the areas at the ends of blocks or at certain corners with house-like buildings containing a few to several units. Higher on the neighborhood scale, more urban versions also have at least two environments but have an opposite mix: they consist mostly of house-like buildings with a few to several units, and a few single-family houses and larger buildings are interspersed. For examples, you can see the way we have used Place Types in the Beaufort County, South Carolina Countywide Development Code Update and in the Cincinnati, Ohio Form-Based Code, which addresses the future of 42 centers and their neighborhoods.

Also, Walters describes the main principles supporting the use of Place Types in zoning. But there’s one not mentioned that could help a lot: physical character. (Perhaps this is what is meant by “images” in the Place Type menu.) Physical character is the sum of the individual parts and what people respond to when they experience an area. It’s not the zoning label or some mundane numerical statistic.

Walkable Urban vs. Auto-Oriented Suburban Contexts

A critical distinction we have found is to understand two contexts—Walkable Urban and Auto-Oriented Suburban—as the different places that they are and not apply one tool or the wrong tool. Each context has different priorities. Each needs different tools and a different approach to zoning.

Walkable Urban contexts are environments where uses are integrated rather than separated and where there is a variety of housing choices within walking distance of shops and services. As the term implies, these areas are set up for walking and biking. Yes, cars are present, but their needs do not take highest priority. Unfortunately, because Walkable Urban contexts are unrecognized in most communities, these areas are required to adjust themselves to and tolerate zoning that is really for the opposite context: Auto-Oriented Suburban.

Auto-Oriented Suburban (Driveable) contexts are environments where uses are separated and driving is the most effective way to get around. Sure, you could walk or bike. But the context isn’t really set up for it. It’s set up for driving. And many people still choose to live and invest their money in these areas. Yes, walkability advocates could try to change minds, but the choice is ultimately up to the people who own those properties. So, after many years of trying to make the same zoning work for what are two completely different places, we decided to make these distinctions clear to the public.

When you map these two distinct contexts, it’s clear to everyone that the places they see as having all of the character—like those Walters mentions in his article—are almost always in the Walkable Urban context. With this information clearly mapped and explained, communities have long-term choices to make. First, should they recognize Walkable Urban contexts and fully serve them with form-based zoning, or try to serve them with use-based zoning? Second, should they recognize Auto-Oriented Suburban contexts and transform some or all to a Walkable Urban context or keep the status quo?

By making these contexts clear, it enables the areas mapped as Walkable Urban contexts to be freed of the irrelevant use-based zoning that typically controls them. It also relieves the pressure on the zoning from needing to accommodate these two distinct places. This allows the conversation to focus on how to best make the zoning to serve the areas that are to continue or transform to the Walkable Urban context. Finally, it raises the community’s appreciation for distinctions and the need for zoning that recognizes distinctions through responsive standards. Most recently, we applied this approach at a very large scale in the Austin, Texas Land Development Code Update (CodeNEXT) and at a smaller, citywide scale in the Vallejo, California Zoning Code Update. Also, to be clear, we use form-based zoning exclusively for Walkable Urban contexts because we find it to be the best zoning when it reflects the realities and needs of the properties it regulates.

We appreciate Walters’ presentation of the “alphabet soup” problem in bringing attention and discussion needed for change that serves people and communities, not archaic systems.